Egyptian mythology is the collection of myths from ancient Egypt, which describe the actions of the Egyptian gods as a means of understanding the cosmos. Myth appears frequently in Egyptian writings and art, particularly in short stories and in religious material such as hymns, ritual texts, funerary texts, and temple decoration. These sources rarely contain a complete account of a myth and often describe only brief fragments. This lack of narrative in myth-related writings has prompted debate among scholars about whether cohesive myths existed in ancient Egyptian culture.

Inspired by the cycles of nature, the Egyptians saw time in the present as a series of recurring patterns, whereas the earliest periods of time were linear. Myths are set in these earliest times, and myth sets the pattern for the cycles of the present. Present events repeat the events of myth, and in doing so renew Ma'at, the fundamental order of the cosmos.

Amongst the most important episodes from the mythic past are the creation myths, in which the gods form the universe out of primordial chaos; the stories of the reign of the sun god Ra upon the earth; and the myth of Osiris and Isis, concerning the struggles of the gods Osiris, Isis, and Horus against the disruptive god Set. Events from the present that might be regarded as myths include Ra's daily journey through the world and its otherworldly counterpart, the Duat. Recurring themes in these mythic episodes include the conflict between the upholders of Ma'at and the forces of disorder, the importance of the pharaoh in maintaining Ma'at, and the continual death and regeneration of the gods.

The details of these sacred events differ greatly from one text to another and often seem contradictory. All Egyptian myths, however, are meant primarily as symbols, expressing the behavior and essence of the mysterious deities in metaphorical terms. Each variant of a myth represents a somewhat different symbolic perspective, enriching the Egyptians' understanding of the gods and the world.

Mythology profoundly influenced Egyptian culture. It formed much of the basis for ancient Egyptian religion, inspiring or influencing many of its rituals and providing the ideological basis for kingship. Scenes and symbols from myth appeared in art in tombs, temples, and amulets. In literature, myths or elements of them were used in stories that range from humor to allegory, demonstrating mythology's prevalence and versatility in Egyptian tradition.

There is some debate among Egyptologists about which of the beliefs in ancient Egypt should be classed as myth. The basic definition of myth suggested by John Baines is "a sacred or culturally central narrative". In Egypt, the narratives central to culture and religion are almost entirely about events among the gods.

Actual narratives about the gods' actions are rare in Egyptian texts, particularly from early periods, and most references to such events are mere mentions or allusions. Some Egyptologists, like Baines, contend that narratives complete enough to be called "myths" existed in all periods, but that Egyptian tradition did not favor writing them down. Others, like Jan Assmann, have argued that true myths were rare in Egypt and may only have emerged partway through its history.

Recently, however, scholars like Vincent Arieh Tobin and Susanne Bickel have suggested that lengthy narration is unnecessary, and even alien to, the complex and flexible nature of Egyptian mythology, because narratives tend toward a simple and fixed perspective on the events they describe. If the requirement for narration is discarded, any statement that conveys an idea about the workings of the cosmos by describing the nature or actions of a god can be called "mythic".

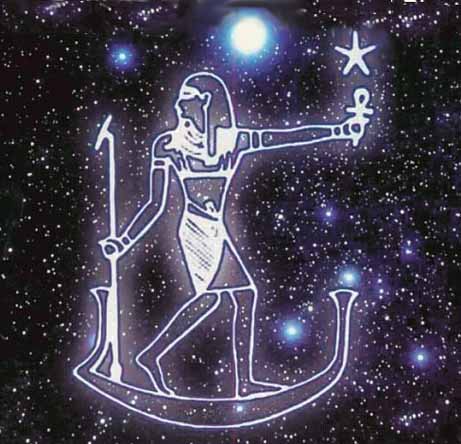

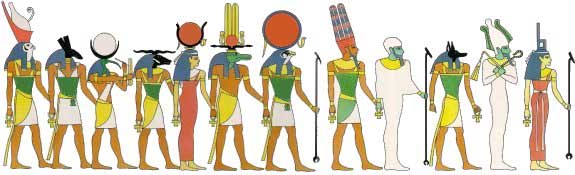

Egyptian Gods and Goddesses

Egyptian deities represent natural phenomena, from physical objects like the earth or the sun to abstract forces like knowledge and creativity. The actions and interactions of the gods, the Egyptians believed, govern the behavior of all of these forces and elements. For the most part, the Egyptians did not describe these mysterious processes in explicit theological writings. Instead, the relationships and interactions of the gods illustrated such processes implicitly.

Most of Egypt's gods, including many of the major ones, do not have significant roles in mythic narratives, although their nature and relationships with other deities are often established in lists or bare statements without narration. For the gods who are deeply involved in narratives, the events of mythology are extremely important expressions of their roles in the cosmos. Therefore, if myth is restricted to narrative, myth is a significant element in Egyptian religious understanding, but not as essential as it is in many other cultures.

The myths are not meant as literal descriptions of the gods or their behavior, although unsophisticated segments of the Egyptian populace may have thought myths were literally true. The events in mythology are symbolic of events that take place in the realm of the gods and that, therefore, are beyond direct human understanding. Symbolism expresses those mysterious processes in a comprehensible way. Not every detail of a mythic account has symbolic significance, however; some images and incidents in primarily religious texts are meant simply as visual or dramatic embellishments of the broader and more meaningful myths to which they have been added.

Much of Egyptian mythology consists of origin myths, explaining the beginnings of various elements of the world, including human institutions and natural phenomena. Kingship is said to have arisen among the gods at the beginning of time and later passed to the human pharaohs; warfare originates when humans begin fighting each other after the sun god's withdrawal into the sky. Myths also describe the supposed beginnings of less fundamental traditions. In a minor mythic episode, the god Horus becomes angry with his mother Isis and cuts off her head. Isis replaces her lost head with that of a cow. This event is apparently meant to explain why Isis was sometimes depicted with the horns of a cow incorporated into her headdress.

Few complete stories appear in Egyptian mythological sources. These sources often contain nothing more than allusions to the events to which they relate, and texts that contain actual narratives tell only portions of a larger story. Thus, for any given myth the Egyptians may have had only the general outlines of a story, from which fragments describing particular incidents were drawn. Moreover, the gods are not well-defined characters, and the motivations for their sometimes inconsistent actions are rarely given. Egyptian myths are not, therefore, well developed tales. Their importance lay in their underlying meaning, not their characteristics as stories. Instead of coalescing into lengthy, fixed narratives, they remained highly flexible and non-dogmatic.

So flexible were Egyptian myths that they could seemingly conflict with each other. Many descriptions of the creation of the world and the movements of the sun occur in Egyptian texts, some very different from each other. The relationships between gods were fluid, so that, for instance, the goddess Hathor could be called the mother, wife, or daughter of the sun god Ra. Separate deities could even be linked as a single being, as the creator god Atum was combined with Ra to form Ra-Atum.

One reason for these apparent inconsistencies is that religious ideas differed over time and in different locations. Gods that were once local patron deities gained national importance with the unification of Egypt around 3100 BC. This event likely inspired myths that linked the local gods into a unified national tradition. The local cults continued to exist, however, and their priests formulated myths that emphasized the importance of their patron gods.

As the influence of different cults shifted, some mythological systems attained national dominance. In the Old Kingdom (c. 2686-2181 BC) the cults of Ra and Atum, centered at Heliopolis, profoundly influenced Egyptian religion. They formed a mythical family, the Ennead, that incorporated the most important deities of the time but gave primacy to Atum and Ra. The Egyptians also overlaid old religious ideas with new ones. For instance, the god Amun was so prominent in the New Kingdom (c.1550-1070 BC) that he was linked with Ra, the older supreme god, and took on many of Ra's roles in the cosmos. In this way the Egyptians produced an immensely complicated set of deities and myths.

Egyptologists in the early twentieth century thought that politically motivated changes like these were the principal reason for the contradictory imagery in Egyptian myth. However, in the 1940s, Henri Frankfort, realizing the symbolic nature of Egyptian mythology, argued that apparently contradictory ideas are part of the "multiplicity of approaches" that the Egyptians used to understand the divine realm. Frankfort's arguments are the basis for much of the more recent analysis of Egyptian beliefs. Political changes affected Egyptian beliefs, but the ideas that emerged through those changes also have deeper meaning. Multiple versions of the same myth express different aspects of the same phenomenon; different gods that behave in a similar way reflect the close connections between natural forces. The varying symbols of Egyptian mythology express ideas too complex to be seen through a single lens.

The Egyptians probably had a tradition of telling myths orally, which may have differed significantly from the written record, but no evidence of this tradition has survived. Modern knowledge of Egyptian myths is drawn from written and pictorial sources. Only a small proportion of these sources has survived to the present, so much of the mythological information that was once written down has been lost. Moreover, such information is not equally abundant in all periods, so the beliefs that Egyptians held in some eras of their history are more poorly understood than the beliefs in better documented times.

The sources that are available range from solemn hymns to entertaining stories. Without a single, canonical version of any myth, the Egyptians adapted general mythic traditions to fit the widely varying purposes of their writings.

Many gods appear in artwork from the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt's history (c. 3100-2686 BC), but little about the gods' actions can be gleaned from these sources because they include minimal writing. The Egyptians began using writing more extensively in the Old Kingdom, in which appeared the first major source of Egyptian mythology: the Pyramid Texts. These texts are a collection of several hundred incantations inscribed in the interiors of pyramids beginning in the 24th century BC. They were the first Egyptian funerary texts, intended to ensure that the kings buried in the pyramid would pass safely through the afterlife. Many of the incantations allude to myths related to the afterlife, including the creation myths and the myth of Osiris. Many of the texts are likely much older than their first known written copies, and they therefore provide clues about the early stages of Egyptian religious belief.

During the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181-2055 BC), the Pyramid Texts developed into the Coffin Texts, which contain similar material and were available to non-royals. Succeeding funerary texts, like the Book of the Dead in the New Kingdom and the Books of Breathing from the Late Period (664-323 BC) and after, developed out of these earlier collections. The New Kingdom also saw the development of another type of funerary text, containing detailed and cohesive descriptions of the nocturnal journey of the sun god. Texts of this type include the Amduat, the Book of Gates, and the Book of Caverns.

Temples, whose surviving remains date mostly from the New Kingdom and later, are another important source of myth. Many temples had a per-ankh, or temple library, storing papyri for rituals and other uses. Among these papyri are hymns, which in the course of praising a god may allude to the god's mythological roles, and texts describing temple rituals, many of which are based partly on myth.

Scattered remnants of these papyrus collections have survived to the present. It is possible that the collections included more systematic records of myths, but no evidence of such texts has survived. Mythological texts and illustrations, containing the same types of material as the known temple papyri, form an important part of the decoration of the temple buildings themselves. The elaborately decorated and well preserved temples of the Ptolemaic and Roman periods (305 BC-AD 380) are an especially rich source of myth.

The Egyptians also performed rituals for personal goals such as protection from or healing of illness. These rituals are often called "magical" rather than religious, but they were believed to work on the same principles as temple rituals, evoking mythical events as the basis for the ritual. The texts for these private rituals often incorporate mythic narratives that adapt the basic outline of a myth, or even create a myth, to fit the specific ritual.

Information from religious sources is limited by a system of traditional restrictions on what they could describe and depict. The murder of the god Osiris, for instance, is never explicitly described in Egyptian writings. The Egyptians believed that words and images could affect reality, so they avoided the risk of making such negative events real.The conventions of Egyptian art were also poorly suited for portraying whole narratives, so most myth-related artwork consists of sparse individual scenes.

References to myth also appear in non-religious Egyptian literature, beginning in the Middle Kingdom. Many of these references are mere allusions to mythic motifs, but several stories are based entirely on mythic narratives. These more direct renderings of myth are particularly common in the Late and Greco-Roman periods. It is unclear whether the use of myth in writing was actually more widespread in those times than earlier, or if the greater number of myth-related texts is simply a result of better overall preservation from those comparatively recent periods. The attitudes toward myth in nonreligious Egyptian texts are variable; some stories resemble the narratives from magical texts, while others are more clearly meant as entertainment and even contain humorous episodes.

A final source of Egyptian myth is the writings of Greek and Roman writers like Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus, who described Egyptian religion in the last centuries of its existence. Prominent among these writers is Plutarch, whose work De Iside et Osiride contains, among other things, the longest ancient account of the myth of Osiris. The information these authors give is affected by their biases about Egypt's culture and may not always accurately reflect Egyptian beliefs.

In Egyptian belief, the disorder that predates the ordered world exists beyond the world as an infinite expanse of formless water, personified by the god Nun. The earth, personified by the god Geb, is a flat piece of land over which arches the sky, usually represented by the goddess Nut. The two are separated by the personification of air, Shu. The sun god Ra is said to travel through the sky, across the body of Nut, enlivening the world with his light. At night Ra passes beyond the western horizon into the Duat, a mysterious region that borders the formlessness of Nun. At dawn he emerges from the Duat in the eastern horizon.

The nature of the sky and the location of the Duat are uncertain. Egyptian texts variously describe the nighttime sun as traveling beneath the earth and within the body of Nut. The Egyptologist James P. Allen believes that these explanations of the sun's movements are dissimilar but coexisting ideas. In Allen's view, Nut represents the visible surface of the waters of Nun, with the stars floating on this surface.

The sun, therefore, sails across the water in a circle, each night passing beyond the horizon to reach the skies that arch beneath the inverted land of the Duat. Leonard H. Lesko, however, believes that the Egyptians saw the sky as a solid canopy and described the sun as traveling through the Duat above the surface of the sky, from west to east, during the night. Joanne Conman, modifying Lesko's model, argues that this solid sky is a moving, concave dome overarching a deeply convex earth. The sun and the stars move along with this dome, and their passage below the horizon is simply their movement over areas of the earth that the Egyptians could not see. These regions would then be the Duat.

The fertile lands of the Nile Valley (Upper Egypt) and Delta (Lower Egypt) lie at the center of the world in Egyptian cosmology. Outside them are the infertile deserts, which are associated with the chaos that lies beyond the world. Somewhere beyond them is the horizon, the akhet. There, two mountains, in the east and the west, mark the places where the sun enters and exits the Duat.

Foreign nations are associated with the hostile deserts in Egyptian ideology. Foreign people, likewise, are generally lumped in with the "nine bows", people who threaten pharaonic rule and the stability of Ma'at, although peoples allied with or subject to Egypt may be viewed more positively. For these reasons, events in Egyptian mythology rarely take place in foreign lands. While some stories pertain to the sky or the Duat, Egypt itself is usually the scene for the actions of the gods. Often, even the myths set in Egypt seem to take place on a plane of existence separate from that inhabited by living humans, although in other stories, humans and gods interact. In either case, the Egyptian gods are deeply tied to their home land.

The Egyptians' vision of time was influenced by their environment. Each day the sun rose and set, bringing light to the land and regulating human activity; each year the Nile flooded, renewing the fertility of the soil and allowing the highly productive agriculture that sustained Egyptian civilization. These periodic events inspired the Egyptians to see all of time as a series of recurring patterns regulated by Ma'at, renewing the gods and the cosmos. Although the Egyptians recognized that different historical eras differ in their particulars, mythic patterns dominate the Egyptian perception of history.

Many Egyptian stories about the gods are characterized as having taken place in a primeval time when the gods were manifest on the earth and ruled over it. After this time, the Egyptians believed, authority on earth passed to human pharaohs. This primeval era seems to predate the start of the sun's journey and the recurring patterns of the present world. At the other end of time is the end of the cycles and the dissolution of the world. Because these distant periods lend themselves to linear narrative better than the cycles of the present, John Baines sees them as the only periods in which true myths take place. Yet, to some extent, the cyclical aspect of time was present in the mythic past as well. Egyptians saw even stories that were set in that time as being perpetually true. The myths were made real every time the events to which they were related occurred.

Ancient Egyptian creation myths are the ancient Egyptian accounts of the creation of the world. The Pyramid Texts, tomb wall decorations and writings, dating back to the Old Kingdom (2780 - 2250 B.C.E) have given us most of our information regarding early Egyptian creation myths. These myths also form the earliest religious compilations in the world. The ancient Egyptians had many creator gods and associated legends. Thus the world or more specifically Egypt was created in diverse ways according to different parts of the country.

In all of these myths, the world was said to have emerged from an infinite, lifeless sea when the sun rose for the first time, in a distant period known as zp tpj, "the first occasion". Different myths attributed the creation to different gods: the set of eight primordial deities called the Ogdoad, the self-engendered god Atum and his offspring, the contemplative deity Ptah, and the mysterious, transcendent god Amun. While these differing cosmogonies competed to some extent, in other ways they were complementary, as different aspects of the Egyptian understanding of creation.

The different creation myths had some elements in common. They all held that the world had arisen out of the lifeless waters of chaos, called Nu. They also included a pyramid-shaped mound, called the benben, which was the first thing to emerge from the waters. These elements were likely inspired by the flooding of the Nile River each year; the receding floodwaters left fertile soil in their wake, and the Egyptians may have equated this with the emergence of life from the primeval chaos. The imagery of the pyramidal mound derived from the highest mounds of earth emerging as the river receded.

The sun was also closely associated with creation, and it was said to have first risen from the mound, as the general sun-god Ra or as the god Khepri, who represented the newly-risen sun. There were many versions of the sun's emergence, and it was said to have emerged directly from the mound or from a lotus flower that grew from the mound, in the form of a heron, falcon, scarab beetle, or human child.

Another common element of Egyptian cosmogonies is the familiar figure of the cosmic egg, a substitute for the primeval waters or the primeval mound. One variant of the cosmic egg version teaches that the sun god, as primeval power, emerged from the primeval mound, which itself stood in the chaos of the primeval sea.

Cosmogonies

The different creation accounts were each associated with the cult of a particular god in one of the major cities of Egypt: Hermopolis, Heliopolis, Memphis, and Thebes. To some degree these myths represent competing theologies, but they also represent different aspects of the process of creation.

The creation myth promulgated in the city of Hermopolis focused on the nature of the universe before the creation of the world. The inherent qualities of the primeval waters were represented by a set of eight gods, called the Ogdoad. The god Nu and his female counterpart Naunet represented the inert primeval water itself; Huh and his counterpart Hauhet represented the water's infinite extent; Kuk and Kauket personified the darkness present within it; and Amun and Amaunet represented its hidden and unknowable nature, in contrast to the tangible world of the living. The primeval waters were themselves part of the creation process, therefore, the deities representing them could be seen as creator gods.

According to the myth, the eight gods were originally divided into male and female groups. They were symbolically depicted as aquatic creatures because they dwelt within the water: the males were represented as frogs, and the females were represented as snakes. These two groups eventually converged, resulting in a great upheaval, which produced the pyramidal mound. From it emerged the sun, which rose into the sky to light the world.

Heliopolis

In Heliopolis, the creation was attributed to Atum, a deity closely associated with Ra, who was said to have existed in the waters of Nu as an inert potential being. Atum was a self-engendered god, the source of all the elements and forces in the world, and the Heliopolitan myth described the process by which he "evolved" from a single being into this multiplicity of elements. The process began when Atum appeared on the mound and gave rise the air god Shu and his sister Tefnut, whose existence represented the emergence of an empty space amid the waters. To explain how Atum did this, the myth uses the metaphor of masturbation, with the hand he used in this act representing the female principle inherent within him.

He is also said to have to have "sneezed" and"spat" to produce Shu and Tefnut, a metaphor that arose from puns on their names. Next, Shu and Tefnut coupled to produce the earth god Geb and the sky goddess Nut, who defined the limits of the world. Geb and Nut in turn gave rise to four children, who represented the forces of life: Osiris, god of fertility and regeneration; Isis, goddess of motherhood; Set, the god of male sexuality; and Nephthys, the female complement of Set. The myth thus represented the process by which life was made possible. These nine gods were grouped together theologically as the Ennead, but the eight lesser gods, and all other things in the world, were ultimately seen as extensions of Atum.

Memphis

The Memphite version of creation centered on Ptah, who was the patron god of craftsmen. As such, he represented the craftsman's ability to envision a finished product, and shape raw materials to create that product. The Memphite theology said that Ptah created the world in a similar way. This, unlike the other Egyptian creations, was not a physical but an intellectual creation by the Word and the Mind of God. The ideas developed within Ptah's heart (regarded by the Egyptians as the seat of human thought) were given form when he named them with his tongue. By speaking these names, Ptah produced the gods and all other things.

The Memphite creation myth coexisted with that of Heliopolis, as Ptah's creative thought and speech were believed to have caused the formation of Atum and the Ennead. Ptah was also associated with Tatjenen, the god who personified the pyramidal mound.

Thebes

Theban theology claimed that Amun was not merely a member of the Ogdoad, but the hidden force behind all things. There is a conflation of all notions of creation into the personality of Amun, a synthesis which emphasizes how Amun transcends all other deities in his being “beyond the sky and deeper than the underworld”. One Theban myth likened Amun's act of creation to the call of a goose, which broke the stillness of the primeval waters and caused the Ogdoad and Ennead to form.

Amun was separate from the world, his true nature was concealed even from the other gods. At the same time, however, because he was the ultimate source of creation, all the gods, including the other creators, were in fact merely aspects of Amun. Amun eventually became the supreme god of the Egyptian pantheon because of this belief.

Amun is synonymous with the growth of Thebes as a major religious capital. But it is the columned halls, obelisks, colossal statues, wall-reliefs and hieroglyphic inscriptions of the Theban temples that we look to gain the true impression of Amun’s superiority. Thebes was thought of as the location of the emergence of the primeval mound at the beginning of time.

In the period of the mythic past after the creation, Ra dwells on earth as king of the gods and of humans. This period is the closest thing to a golden age in Egyptian tradition, the period of stability that the Egyptians constantly sought to evoke and imitate. Yet the stories about Ra's reign focus on conflicts between him and forces that disrupt his rule, reflecting the king's role in Egyptian ideology as enforcer of Ma'at.

In an episode known in different versions from temple texts, some of the gods defy Ra's authority, and he destroys them with the help and advice of other gods like Thoth and Horus the Elder. At one point he faces dissent even from an extension of himself, the Eye of Ra, which can act independently of him in the form of a goddess. The Eye goddess becomes angry with Ra and runs away from him, wandering wild and dangerous in the lands outside Egypt. Weakened by her absence, Ra sends one of the other gods - Shu, Thoth, or Anhur, in different accounts - to retrieve her, by force or persuasion. Because the Eye of Ra is associated with the star Sothis, whose heliacal rising signaled the start of the Nile flood, the return of the Eye goddess to Egypt coincides with the life-giving inundation. Upon her return, the goddess becomes the consort of Ra or of the god who has retrieved her. Her pacification restores order and renews life.

As Ra grows older and weaker, humanity, too, turns against him. In an episode often called "The Destruction of Mankind", related in The Book of the Heavenly Cow, Ra discovers that humanity is plotting rebellion against him and sends his Eye to punish them. She slays many people, but Ra apparently decides that he does not want her to destroy all of humanity. He has beer dyed red to resemble blood and spreads it over the field. The Eye goddess drinks the beer, becomes drunk, and ceases her rampage. Ra then withdraws into the sky, weary of ruling on earth, and begins his daily journey through the heavens and the Duat. The surviving humans are dismayed, and they attack the people among them who plotted against Ra. This event is the origin of warfare, death, and humans' constant struggle to protect Ma'at from the destructive actions of other people.[58]

In The Book of the Heavenly Cow, the results of the destruction of mankind seem to mark the end of the direct reign of the gods and of the linear time of myth. The beginning of Ra's journey is the beginning of the cyclical time of the present. Yet in other sources, mythic time continues after this change. Egyptian accounts give sequences of divine rulers who take the place of the sun god as king on earth, each reigning for many thousands of years. Although accounts differ as to which gods reigned and in what order, the succession from Ra-Atum to his descendants Shu and Geb - in which the kingship passes to the male in each generation of the Ennead - is common. Both of them face revolts that parallel those in the reign of the sun god, but the revolt that receives the most attention in Egyptian sources is the one in the reign of Geb's heir Osiris.

The collection of episodes surrounding Osiris' death and succession is the most elaborate of all Egyptian myths, and it had the most widespread influence in Egyptian culture. In the first portion of the myth, Osiris, who is associated with both fertility and kingship, is killed and his position usurped by his brother Set.

In some versions of the myth, Osiris is actually dismembered and the pieces of his corpse scattered across Egypt. Osiris' sister and wife, Isis, finds her husband's body and restores it to wholeness. She is assisted by funerary deities such as Nephthys and Anubis, and the process of Osiris' restoration reflects Egyptian embalming and funerary practices. Isis then briefly revives Osiris to conceive an heir with him: the god Horus.

The next portion of the myth concerns Horus' birth and childhood. Isis gives birth to and raises her son in secluded places, hidden from the menace of Set. The episodes in this phase of the myth concern Isis' efforts to protect her son from Set or other hostile beings, or to heal him from sickness or injury. In these episodes Isis is the epitome of maternal devotion and a powerful practitioner of healing magic.

In the third phase of the story, Horus competes with Set for the kingship. Their struggle encompasses a great number of separate episodes and ranges in character from violent conflict to a legal judgment by the assembled gods.

In one important episode, Set tears out one or both of Horus' eyes, which are later restored by the healing efforts of Thoth or Hathor. For this reason, the Eye of Horus is a prominent symbol of life and well-being in Egyptian iconography. Because Horus is a sky god, with one eye equated with the sun and the other with the moon, the destruction and restoration of the single eye explains why the moon is less bright than the sun.

Texts present two different resolutions for the divine contest: one in which Egypt is divided between the two claimants, and another in which Horus becomes sole ruler. The former version may reflect the resolution of a conflict between regions of Egypt in the Protodynastic or Early Dynastic eras, although which regions the two gods represent is uncertain.

In the latter version, the ascension of Horus, Osiris' rightful heir, symbolizes the reestablishment of Ma'at after the unrighteous rule of Set. With order restored, Horus can perform the funerary rites for his father that are his duty as son and heir. Through this service Osiris is given new life in the Duat, whose ruler he becomes. The relationship between Osiris as king of the dead and Horus as king of the living stands for the relationship between every king and his deceased predecessors. Osiris, meanwhile, represents the regeneration of life. On earth he is credited with the annual growth of crops, and in the Duat he is involved in the rebirth of the sun and of deceased human souls.

Although Horus to some extent represents any living pharaoh, he is not the end of the lineage of ruling gods. He is succeeded first by gods and then by spirits that represent dim memories of Egypt's Predynastic rulers, the souls of Nekhen and Pe. They link the entirely mythical rulers to the final part of the sequence, the lineage of Egypt's historical kings.

Several disparate Egyptian texts address a similar theme: the birth of a divinely fathered child who is heir to the kingship. The earliest known appearance of such a story does not appear to be a myth but an entertaining folktale, found in the Middle Kingdom Westcar Papyrus, about the birth of the first three kings of Egypt's Fifth Dynasty. In that story, the three kings are the offspring of Ra and a human woman.

The same theme appears in a firmly religious context in the New Kingdom, when the rulers Hatshepsut, Amenhotep III, and Ramsses II depicted in temple reliefs their own conception and birth, in which the god Amun is the father and the historical queen the mother. By stating that the king originated among the gods and was deliberately created by the most important god of the period, the story gives a mythological background to the king's coronation, which appears alongside the birth story. The divine connection legitimizes the king's rule and provides a rationale for his role as intercessor between gods and humans.

Similar scenes appear in many post-New Kingdom temples, but this time the events they depict involve the gods alone. In this period, most temples were dedicated to a mythological family of deities, usually a father, mother, and son. In these versions of the story, the birth is that of the son in each triad. Each of these child gods is the heir to the throne, who will restore stability to the country. This shift in focus from the human king to the gods who are associated with him reflects a decline in the status of the pharaoh in the late stages of Egyptian history.

Ra's movements through the sky and the Duat are not fully narrated in Egyptian sources, although funerary texts like the Amduat, Book of Gates, and Book of Caverns relate the nighttime half of the journey in sequences of vignettes. This journey is key to Ra's nature and to the sustenance of life in the cosmos.

In traveling across the sky, Ra brings light to the earth, sustaining all things that live there. He reaches the peak of his strength at noon and then ages and weakens as he moves toward sunset. In the evening, Ra takes the form of Atum, the creator god, oldest of all things in the world. According to early Egyptian texts, at the end of the day he spits out all the other deities, whom he devoured at sunrise. Here they represent the stars, and the story explains why the stars are visible at night and seemingly absent during the day.

At sunset Ra passes through the akhet, the horizon, in the west. At times the horizon is described as a gate or door that leads to the Duat. At others, the sky goddess Nut is said to swallow the sun god, so that his journey through the Duat is likened to a journey through her body.

In funerary texts, the Duat and the deities in it are portrayed in elaborate, detailed, and widely varying imagery. These images are symbolic of the awesome and enigmatic nature of the Duat, where both the gods and the dead are renewed by contact with the original powers of creation. Indeed, although Egyptian texts avoid saying it explicitly, Ra's entry into the Duat is seen as his death.

Certain themes appear repeatedly in depictions of the journey. Ra overcomes numerous obstacles in his course, representative of the effort necessary to maintain Ma'at. The greatest challenge is the opposition of Apep, a serpent god who represents the destructive aspect of disorder, and who threatens to destroy the sun god and plunge creation into chaos.

In many of the texts, Ra overcomes these obstacles with the assistance of other deities who travel with him; they stand for various powers that are necessary to uphold Ra's authority. In his passage Ra also brings light to the Duat, enlivening the blessed dead who dwell there. In contrast, his enemies - people who have undermined Ma'at -are tormented and thrown into dark pits or lakes of fire.

The key event in the journey is the meeting of Ra and Osiris. In the New Kingdom, this event developed into a complex symbol of the Egyptian conception of life and time. Osiris, relegated to the Duat, is like a mummified body within its tomb. The ever-moving Ra is like the ba, or soul, of a deceased human, which may travel during the day but must return to its body each night. When Ra and Osiris meet, they merge into a single being. Their pairing reflects the Egyptian vision of time as a continuous repeating pattern, with one member (Osiris) being always static and the other (Ra) living in a constant cycle.

Once he has united with Osiris' regenerative power, Ra continues on his journey with renewed vitality. This renewal makes possible Ra's emergence at dawn, which is seen as the rebirth of the sun - expressed by a metaphor in which Nut gives birth to Ra after she has swallowed him - and the repetition of the first sunrise at the moment of creation. At this moment, the rising sun god swallows the stars once more, absorbing their power. In this revitalized state, Ra is depicted as a child or as the god Khepri, both of which represent rebirth in Egyptian iconography.

Egyptian texts typically treat the dissolution of the world as a possibility to be avoided, and for that reason they do not often describe it in detail. However, many texts allude to the idea that the world, after countless cycles of renewal, is destined to end.

This end is described in a passage in the Coffin Texts and a more explicit one in the Book of the Dead, in which Atum says that he will one day dissolve the ordered world and return to his primeval, inert state within the waters of chaos. All things other than the creator will cease to exist, except Osiris, who will survive along with him.

Details about this eschatological prospect are left unclear, including the fate of the dead who are associated with Osiris. Yet with the creator god and the god of renewal together in the waters that gave rise to the cosmos, there is the potential for a new creation to arise in the same manner as the old.

Because the Egyptians rarely described theological ideas explicitly, the implicit ideas of mythology formed much of the basis for Egyptian religious belief. The purpose of Egyptian religion was the maintenance of Ma'at, and the concepts that myths express were believed to be essential to Ma'at. The rituals of Egyptian religion were meant to make the mythic events, and the concepts they represented, real once more, thereby renewing Ma'at. The rituals were believed to achieve this effect through the force of heka, the same connection between the physical and divine realms that enabled the original creation.

For this reason, Egyptian rituals often included actions that symbolized mythological events. Temple rites included the destruction of models representing malign gods like Set or Apophis, private magical spells called upon Isis to heal the sick as she did for Horus, and funerary practices evoked the myth of Osiris' resurrection.

Yet rituals rarely, if ever, involved reenactment of entire mythic narratives. Many ritual activities were focused on more basic activities like giving offerings to the gods, with mythic themes serving as ideological background rather than as the focus of a rite. Nevertheless, myth and ritual strongly influenced each other: myths could inspire rituals, and rituals that did not originally have a mythological meaning could be reinterpreted as having one.

Kingship was a key element of Egyptian religion, through the king's role as link between humanity and the gods. Myths explain the background for this connection between royalty and divinity. The myths about the Ennead establish the king as heir to the lineage of rulers reaching back to the creator; the myth of divine birth states that the king is the son and heir of a god; and the myths about Osiris and Horus emphasize that rightful succession to the throne is essential to the maintenance of Ma'at. Thus, mythology provided the rationale for the very nature of Egyptian government.

Illustrations of gods and mythological events appear extensively alongside religious writing in tombs, temples, and funerary texts. As stated above, mythological scenes in Egyptian artwork are rarely placed in sequence as a narrative, but such scenes, particularly depicting the resurrection of Osiris, do sometimes appear individually in religious artwork.

Oblique mythological allusions were very widespread in Egyptian art and architecture. In temple design, the central path of the temple axis was likened to the sun god's path across the sky, and the sanctuary at the end of the path represented the place of creation from which he rose. Temple decoration was replete with solar emblems that underscored this relationship.

Similarly, the corridors of tombs were linked with the god's journey through the Duat, and the burial chamber with the tomb of Osiris. The pyramid, the best-known of all Egyptian architectural forms, may have been inspired by mythic symbolism, for it represented the mound of creation and the original sunrise, appropriate associations for a monument intended to assure the owner's rebirth after death.

Symbols in Egyptian tradition were subject to a great deal of reinterpretation, so that the meanings of mythical symbols could change and multiply over time like the myths themselves.

More ordinary works of art were also designed to evoke mythic themes, like the amulets that Egyptians commonly wore to invoke divine powers. The Eye of Horus, for instance, was a very common shape for protective amulets because it represented Horus' well-being after the restoration of his lost eye. Scarab-shaped amulets symbolized the regeneration of life, referring to the form that Ra was said to take at dawn.

Themes and motifs from mythology appear frequently in Egyptian literature, even outside of religious writings. An early instruction text, the "Teaching for King Merykara" from the Middle Kingdom, contains a brief reference to a myth of some kind, possibly the Destruction of Mankind; the earliest known Egyptian short story, "Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor", incorporates ideas about the gods and the eventual dissolution of the cosmos into a story set in the past. Some later stories derive much of their plot from mythological events: "Tale of the Two Brothers" adapts the myth of Osiris into a fantastic story about ordinary people, and "The Blinding of Truth by Falsehood" transforms the conflict between Horus and Set into an allegory.

Non-religious texts directly describing events among the gods may have appeared as early as the Middle Kingdom, and such texts are particularly abundant from the Late and Greco-Roman periods. Although these texts are more clearly derived from myth than those mentioned above, they still adapt the myths for non-religious purposes. "The Contendings of Horus and Seth" tells the story of the conflict between the two gods, often with a humorous and seemingly irreverent tone. "The Myth of the Eye of the Sun" incorporates fables into an entirely myth-based framing story.

Literary purposes could also affect the mythic narratives found in magical texts, as with "Isis, the Rich Woman's Son, and the Fisherman's Wife", which incorporates a moral message unrealated to its magical purpose. The varying attitudes and functions of these texts demonstrate the wide range of purposes that myth was adapted to serve in Egyptian culture.