The earliest undisputed human burial, discovered so far, dates back 100,000 years. Human skeletal remains stained with red ochre were discovered in the Skhul cave at Qafzeh, Israel. A variety of grave goods were present at the site, including the mandible of a wild boar in the arms of one of the skeletons.

Prehistoric cemeteries are referred to by the more neutral term grave field. They are one of the chief sources of information on prehistoric cultures, and numerous archaeological cultures are defined by their burial customs, such as the Urnfield culture of the European Bronze Age. Read more ...

The mystery of hanging coffins: Are modern Bo people the genetic heirs of an ancient burial tradition? PhysOrg - November 25, 2025

A new study has uncovered a direct genetic link between ancient practitioners of the Hanging Coffin burial tradition and the modern Bo people in Southwest China. The findings offer unprecedented insight into the deep ancestral origins and migratory history associated with this unique mortuary practice. The Hanging Coffin practice, characterized by the placement of wooden coffins on cliffs or in caves, has historically been ascribed to the Bo ethnic group, which is believed to have disappeared after the Ming Dynasty.

Copper Age burials holding the remains of elite women and elaborate pouches decorated with hundreds of animal teeth have been discovered in Germany. Live Science - August 7, 2025

Israel: New analysis of the Skhul I skull: One of the oldest human burials in the world dating back to ca. 140,000 years ago PhysOrg - July 10, 2025

In 1931, the 'Skhul I' fossil was uncovered at Mugharat es-Skhul (the Cave of the Children), also known as Skhul Cave, Israel. It forms part of the oldest intentional human burials ever discovered, dating back to ca. 140,000 years ago. For decades, it became the topic of much debate over its taxonomic classification. Today it is widely attributed to Homo sapiens.

Stone Age tombs for Irish royalty aren't what they seem, new DNA analysis reveals Live Science - April 18, 2025

A reanalysis of ancient DNA shows that a major cultural change took place in Ireland after four centuries of farming. Archaeologists have long assumed that Stone Age tombs in Ireland were built for royalty. But a new analysis of DNA from 55 skeletons found in these 5,000-year-old graves suggests that the tombs were made for the community, not for a ruling dynasty.

Stunning reconstruction reveals warrior and his weapons from 4,000-year-old burial in Siberia Live Science - April 6, 2025

A new reconstruction reveals the face, shield and weapons of a late Stone Age warrior, whose remains were found in a 4,000-year-old burial in Siberia.

The Oldest Known Burial Site in The World - Found in South Africa - Wasn't Created by Our Species but by Homo naledi a tree-climbing Stone Age hominid Science Alert - June 20, 2024

The findings challenge the current understanding of human evolution, as it is normally held that the development of bigger brains allowed for the performing of complex, "meaning-making" activities such as burying the dead.

Russian farmer unearths the remains of a 2,000-year-old nomadic 'royal' buried alongside a 'laughing' man with an egg-shaped head and a haul of jewelry, weapons and animal sacrifices Daily Mail - May 15, 2019

A farmer digging a pit on his land unearthed 2,000-year-old treasure inside the ancient burial mound of the tomb of a nomadic 'royal', along with a 'laughing' man with an artificially deformed egg-shaped skull. Stunning gold and silver jewelry, weaponry, valuables and artistic household items were found next to the chieftain's skeleton in a grave close to the Caspian Sea in southern Russia. Local farmer Rustam Mudayev's spade made an unusual noise and it emerged he had struck an ancient bronze pot near his village of Nikolskoye in Astrakhan region.

Archaeologists find the oldest burials in Ecuador PhysOrg - November 27, 2018

Archaeologists of the Far Eastern Federal University (FEFU) found three burials of the ancient inhabitants of South America dated from 6 to 10 thousand years ago. The excavations were carried out in Atahualpa anton, Ecuador. The findings belong to the Las Vegas archeological culture of the Stone Age. Analysis of artifacts will help scientists understand the development of ancient cultures on the shores of the Pacific Ocean and clarify the origin and development of ancient American civilizations,

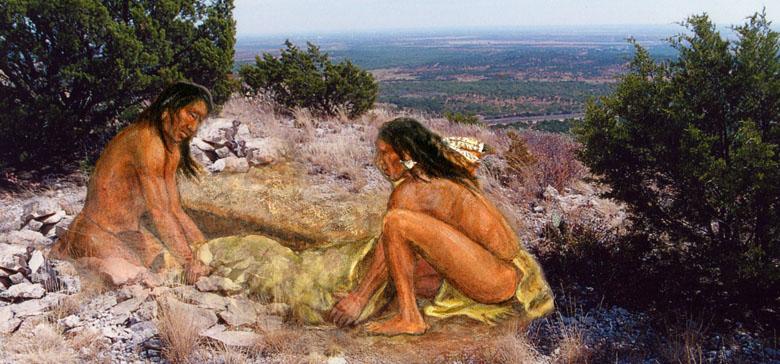

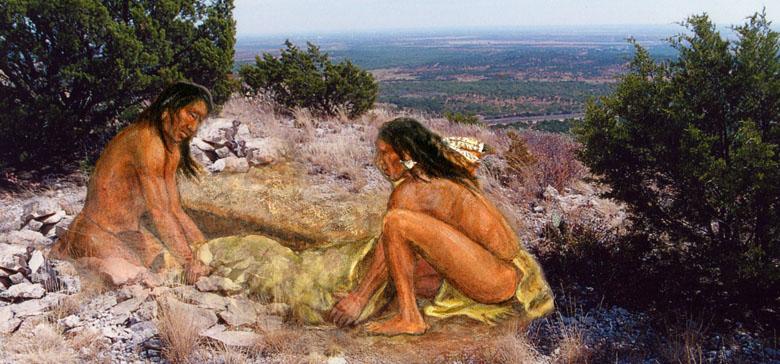

Broken pebbles offer clues to Paleolithic funeral rituals PhysOrg - February 9, 2017

Humans may have ritualistically "killed" objects to remove their symbolic power, some 5,000 years earlier than previously thought, a new international study of marine pebble tools from an Upper Paleolithic burial site in Italy suggests. Researchers concluded that some 12,000 years ago the flat, oblong pebbles were brought up from the beach, used as spatulas to apply ochre paste to decorate the dead, then broken and discarded.

Remains Found of 7,000-Year-Old Man Buried Upright Live Science - February 17, 2016

A Mesolithic site in Germany has revealed the 7,000-year-old remains of a young man buried there in a strange upright position. Placed in a vertical pit, the body was fixed upright by filling the grave with sand up to the knees. The upper body was left to decay and was likely picked at by scavengers. The unique burial was found near the village of Gro§ Fredenwalde, on top of a rocky hill in northeastern Germany, about 50 miles north of Berlin.

Neolithic tomb reveals community stayed together, even in death PhysOrg - January 23, 2016

A Neolithic Spanish burial site contains remains of a closely-related local community from 6000 years ago. The Neolithic people are thought to have introduced new burial rituals in the modern-day Europe. This included building megalithic tombs, which were used over an extended period of time as collective burial sites and venues for ritual acts. The authors of this study examined a megalithic tomb at Alto de Reinoso in Northern Spain to build a comprehensive picture of this community using archaeological analysis, genetics, isotope analysis, and bone analysis.

Red Lady cave burial reveals Stone Age secrets New Scientist - March 18, 2015

Some 19,000 years ago, a woman was coated in red ochre and buried in a cave in northern Spain. What do her remains say about Paleolithic life in western Europe? She was privileged to have a tombstone, and her grave may have been adorned with flowers. But the many who, for millennia after her death, took shelter in El Miron cave in northern Spain must have been unaware of the prestigious company they were keeping.

Buried in a side chamber at the back of the cave is a very special Palaeolithic woman indeed. Aged between 35 and 40 when she died, she was laid to rest alongside a large engraved stone, her body seemingly daubed in sparkling red pigment. Small, yellow flowers may even have adorned her grave 18,700 years ago - a time when cave burials, let alone one so elaborate, appear to have been very rare. It was a momentous honour, and no one knows why she was given it.

The Red Lady, as researchers are calling her, was a member of the Magdalenian people of the late Upper Palaeolithic. They would have been anatomically just like us, they had clothes and probably language, too, and belonged to social networks that spread across Europe. But although they lived in large numbers in Portugal and Spain, and archaeologists have been searching for burial sites for nearly 150 years, the Red Lady's grave is the first Magdalenian burial found in the Iberian peninsula.

The Magdalenian age saw a real explosion in the number and abundance of art, and in the realism of the animals represented," says Straus, especially in sites in northern Spain and France. The El Miron cave has its share, including an engraving of a horse and possibly one of a bison too. But most intriguing are the lines scratched upon the 2-metre-wide block of limestone behind which the Red Lady was buried. What looks like a mess of fine, straight lines could actually be far more significant.

Dozens of researchers have been excavating El Miron since 1996, with around 20 working on the Red Lady's grave since it was found. When they began digging, they discovered the jawbone (see picture) and shin bone (tibia) almost immediately. Both were bright red Ð although they have since faded Ð a sign that the woman had been covered in red ochre, a specially prepared iron oxide pigment that humans appear to have slathered on their dead for thousands of years. "It goes back to pre-Homo sapiens," says Straus. "This is a color that in their lives must have been very spectacular," he says, suggesting that its blood-like hue may have symbolized life and death.

The people who buried her used a special form of ochre, not from local sources, that sparkled with specular hematite, a form of iron oxide. It may have been applied to her corpse or clothes as a preservative or as a ritual. The regular use of red ochre at burials throughout the Upper Paleolithic elsewhere in Europe implies this formed part of a burial rite, says William Davies of the University of Southampton, UK. "It is certainly possible that these people held spiritual beliefs," Davies says.

But the skeleton is incomplete, a fact that may be linked to gnaw-marks on the tibia left behind. The pattern of black manganese oxide, which forms on bones as bodies rot, shows that a carnivore Ð about the size of a dog or wolf Ð took to the tibia some time after the flesh had decomposed. After this incident, a number of large bones, including the cranium, seem to have been removed, perhaps for display or reburial elsewhere. Many of the remaining bones, including the tibia and jawbone, were treated once again with red ochre, possibly to resanctify them

Prehistoric Grave May Be Earliest Example of Death During Childbirth Live Science - February 4, 2015

Archaeologists say they've made a grim discovery in Siberia: the grave of a young mother and her twins, who all died during a difficult childbirth about 7,700 years ago. The finding may be the oldest confirmed evidence of twins in history and one of the earliest examples of death during childbirth, the researchers say. The grave was first excavated in 1997 at a prehistoric cemetery in Irkutsk, a Russian city near the southern tip of Lake Baikal, the oldest and deepest freshwater lake in the world. The cemetery has been dubbed Lokomotiv because it was exposed in the base of a hill that was being carved out during construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway in 1897.

Prehistoric Cemetery Reveals Man and Fox Were Pals Live Science - February 3, 2011

Before dog was man's best friend, we might have kept foxes as pets, even bringing them with us into our graves, scientists now say. This discovery, made in a prehistoric cemetery in the Middle East, could shed light on the nature and timing of newly developing relationships between people and beasts before animals were first domesticated. It also hints that key aspects of ancient practices surrounding death might have originated earlier than before thought.

Bronze Age People Left Flowers at Grave PhysOrg - December 16, 2009

Archaeologists from the Universities of Glasgow and Aberdeen have found proof that pre-historic people laid flowers at the graves of their dead. Experts believe the discovery of a bunch of meadowsweet blossoms in a Bronze Age grave in Forteviot, Perthshire is the first recorded example of such a ceremony.

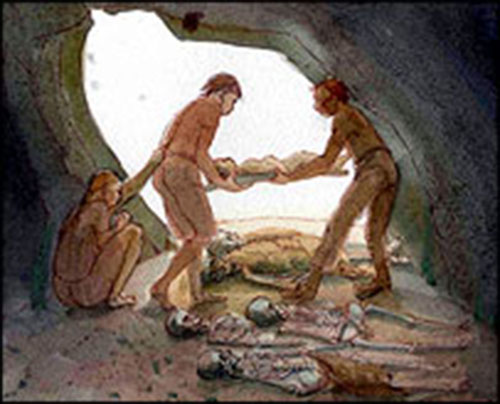

Oldest nuclear family 'murdered' BBC - November 18, 2008

The oldest genetically identifiable nuclear family met a violent death, according to analysis of remains from 4,600-year-old burials in Germany. Writing in the journal PNAS, researchers say the broken bones of these stone age people show they were killed in a struggle. Comparisons of DNA from one grave confirm it contained a mother, father, and their two children.

The son and daughter were buried in the arms of their parents. In total, the four graves contain 13 bodies, eight children aged six months to nine years and five adults aged 25 to 60. In two graves, DNA was well preserved, which allowed comparisons between the occupants. One of these contained the nuclear family, while the other grave contained three related children and an unrelated woman. The researchers suggest she may have been an aunt or stepmother. These stone age people are thought to belong to a group known as the Corded Ware Culture, signified by their pots decorated with impressions from twisted cords. In their burial culture all bodies usually face south. In the family grave the adults did face south, but the children they hold in their arms face towards them. The researchers say an exception to the cultural norm was made so as to express the biological relationship.

Discovery Of The Oldest Remains Of A Woman Who Died In Childbirth Science Daily - October 7, 2004

In ancient times, female death rates were particularly high and generally related to problems in maternity, such as complications during pregnancy, childbirth or the period of breast-feeding. However, in most cases this link has only been established from indirect data, such paleodemographic data and ethnographic references, or based on the poor health conditions normally attributed to ancient human groups. There also exists direct archaeological evidence of the high rate of female mortality in the child-rearing period. However, it has not always been possible to establish the cause of death in females and whether or not there was any relation to obstetric complications.

Evidence of earliest human burial BBC - March 23, 2003

Scientists claim they have found the oldest evidence of human creativity: a 350,000-year-old pink stone axe. The handaxe, which was discovered at an archaeological site in northern Spain, may represent the first funeral rite by human beings. It suggests humans were capable of symbolic thought at a far earlier date than previously thought. Spanish researchers found the axe among the fossilized bones of 27 ancient humans that were clumped together at the bottom of a 14-metre- (45 feet) deep pit inside a network of limestone caves at Atapuerca, near Burgos. It is the only man-made implement found in the pit. It may confirm the team's belief that other humans deposited bodies in the pit deliberately.