Cuneiform script is one of the earliest known forms of written expression. Emerging in Sumer around the 30th century BC, with predecessors reaching into the late 4th millennium (the Uruk IV period), cuneiform writing began as a system of pictographs. In the course of the 3rd millennium BC the pictorial representations became simplified and more abstract.

The number of characters in use also grew gradually smaller, from about 1,000 unique characters in the Early Bronze Age to about 400 unique characters in Late Bronze Age Hittite cuneiform. Cuneiform writing was gradually replaced by alphabetic writing in the Iron Age Neo-Assyrian Empire and was practically extinct by the beginning of the Common Era. It was deciphered from scratch in 19th century scholarship.

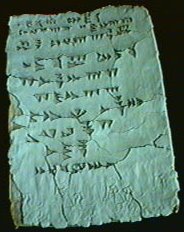

Cuneiform documents were written on clay tablets, by means of a blunt reed for a stylus. The impressions left by the stylus were wedge shaped, thus giving rise to the name cuneiform ("wedge shaped," from the Latin cuneus, meaning "wedge").

The Sumerian script was adapted for the writing of the Akkadian, Eblaite, Elamite, Hittite, Luwian, Hattic, Hurrian, and Urartian languages, and it inspired the Ugaritic and Old Persian national alphabets.

In the late fourth and third milleniums B.C. a people called the Sumerians began to develop a writing system called "cuneiform" ("wedge-shaped"), written on wet clay with a sharpened stick, or stylus. At first the Sumerians used a series of pictures ("pictograms") to record information having to do with business and administration, but went on to develop a system of symbols that stood for ideas and later sounds (usually syllables). In the later stages of Sumerian writing there were about 600 signs that were used on a regular basis.

The language that the Sumerians used is not related to any other language we know about, and it gradually ceased to be a spoken language. The writing system, however, was adopted by people speaking a Semitic language called Akkadian, and continued to be used by a number of peoples up until the 1st century B.C.E. Both the Babylonians and Assyrians, who spoke dialects of Akkadian, used the cuneiform signs, writing not only in their own languages, but sometimes in Sumerian as well. Sumerian had become the language of literature and scholarship, somewhat like Latin up until fairly recently.

Cuneiform tablets have also been found in Eblaite (a Semitic language from northern Syria), Elamite (from the area of modern Iran), Hittite (an Indo-European language spoken in ancient Turkey), and other languages throughout the ancient Near East.

The tablet illustrated here is a business document with a seal impression. Seal impressions are somewhat like signatures, in that they identify the person involved in the business transaction recorded on the tablet. While most of the tablets that have been found are such things as contracts, sales receipts, and tax records, a number of very important literary texts have been found as well, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Code of Hammurabi.

The earliest attested documents in cuneiform were written in Sumerian, the language of the inhabitants of southern Mesopotamia and Chaldea from the 4th until the 2nd millennium BC.

Discovered at the site of the ancient city of Uruk (biblical Erech), they were in a pictographic type of cuneiform in which objects were represented by pictures, numbers were represented by the repetitional use of strokes or circles, and proper names were indicated by combinations of pictures used according to the rebus principle; i.e., the pictures were to be interpreted according to their usual pronunciations rather than according to the objects they depicted.

During the 3rd millennium BC the pictures gradually changed to conventionalized linear drawings and, because they were pressed into soft clay tablets with the slanted edge of a stylus, came to have a wedge-shaped appearance.

Earlier cuneiform was written in columns from top to bottom but during the 3rd millennium came to be written from left to right with the cuneiform signs turned on their sides.

At about the same time these changes in the cuneiform writing system were occurring, it was adopted by the Akkadians, Semitic invaders of Mesopotamia, for writing their language. The earliest Akkadian cuneiform inscriptions date from the Old Akkadian or Early Akkadian period (c. 2450 to c. 1850 BC), during which the inscriptions of Sargon, the great ruler of Akkad, were written. Cuneiform continued to be used for writing the Assyrian and Babylonian dialects descended from Akkadian.

Cuneiform was borrowed by the Elamites, the Kassites, the Persians, the Mitanni, and the Hurrians. The Hurrians passed the cuneiform writing system on to the Hittites, who spoke an Indo-European language; cuneiform was also used for the languages (e.g., Luwian, Hattian) spoken in areas under Hittite control.

With the spread of Aramaic as the lingua franca of the Near East in the 7th and 6th centuries BC, the increasing use of the Phoenician script, and the loss of political independence in Mesopotamia with the growth of the Persian Empire, cuneiform came to be used less and less, although it continued to be written by many conservative priests and scholars for several more centuries.

The latest known tablet in cuneiform dates from c. AD 75.

The Old Persian part of the trilingual royal inscriptions of the Achaemenid kings of Persia were the first cuneiform documents to be deciphered. The inscriptions were also written in Elamite, which still has not been completely deciphered and investigated, and Akkadian, which was deciphered as soon as scholars recognized it to be a Semitic language.

Once Akkadian had been deciphered, the complete cuneiform system became intelligible and the other languages written in cuneiform could be read. Sumerian, at first believed to be a special way of writing Akkadian rather than a separate language, was among the last of the languages written in cuneiform to be deciphered.

Encyclopedia Britannica

Cuneiform Script Wikipedia

Cuneiform Tablets Google Videos

Cuneiform Tablets Google Videos

Fragment of a clay tablet from the library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh, with an Assyrian account of the Flood.

In ancient times writing was done on papyrus, parchment, potsherds, and clay tablets. The latter were made of clean-washed, smooth clay. While still wet, the clay had wedge-shaped letters (now called "cuneiform" from Latin cuneus, "wedge") imprinted on it with a stylus, and then was kiln fired or sun dried. Tablets were made of various shapes - cone-shaped, drum-shaped, and flat. They were often placed in a clay envelop. Vast quantities of these have been excavated in the Near East, of which about a half million are yet to be read. It is estimated that 99 percent of the Babylonian tablets have yet to be dug. The oldest ones go back to 3000 B.C. They are practically imperishable; fire only hardens them more. Personal and business letters, legal documents, books, and communications between rulers are represented.

One of the most famous is the Code of Hammurabi, a Babylonian king who lived long before the time of Moses. The tablets reveal intimate details of everyday life in the Near East and shed light on many obscure customs mentioned in Old Testament. Some tell the story of the Creation, the Fall, and the Flood.

A Babylonian tablet from 87 B.C. repots the arrival of the Halley's comet.

An early world map, circa 600 B.C., shows Babylon as a rectangle intersected by two vertical lines representing the Euphrates River. Small circle stand for surrounding kingdoms, and an ocean encircles the world.

The inscribed clay tablets from the ancient city of Ugarit (ca. 1300 B.C.) are the most important source of information about ancient Canaanite culture that we possess. Not only have they opened an extraordinary door into Canaanite civilization, but they have played an enormous role in gaining an understanding of ancient Israelite religion, since Israel developed out of Canaanite culture.

The Ugaritic language, discovered by French archaeologists in 1928, is known only in the form of writings found in the lost city of Ugarit, near the modern village of Ras Shamra, Syria. It has been extremely important for scholars of the Old Testament in clarifying Biblical Hebrew texts and has revealed more of the way in which ancient Israelite culture finds parallels in the neighboring cultures.

Ugaritic was "the greatest literary discovery from antiquity since the deciphering of the Egyptian hieroglyphs and Mesopotamian cuneiform".

Literary texts discovered at Ugarit include the Legend of Keret, the Aqhat Epic (or Legend of Danel), the Myth of Baal-Aliyan, and the Death of Baal - the latter two are also collectively known as the Baal Cycle - all revealing a Canaanite mythology.

The Ugaritic language is attested in texts from the 14th through the 12th century BC.[2] The city was destroyed in 1180/70 BC.

PhysOrg - March 31, 2008

The giant landslide centred at Kšfels in Austria is 500m thick and five kilometres in diameter and has long been a mystery since geologists first looked at it in the 19th century. The conclusion drawn by research in the middle 20th century was that it must be due to a very large meteor impact because of the evidence of crushing pressures and explosions. But this view lost favour as a much better understanding of impact sites developed in the late 20th century. In the case of Kšfels there is no crater, so to modern eyes it does not look as an impact site should look. However, the evidence that puzzled the earlier researchers remains unexplained by the view that it is just another landslide.

This new research by Alan Bond, Managing Director of Reaction Engines Ltd and Mark Hempsell, Senior Lecturer in Astronautics at Bristol University, brings the impact theory back into play. It centres on another 19th century mystery, a Cuneiform tablet in the British Museum collection No K8538 (known as "the Planisphere").

It was found by Henry Layard in the remains of the library in the Royal Place at Nineveh, and was made by an Assyrian scribe around 700 BC. It is an astronomical work as it has drawings of constellations on it and the text has known constellation names. It has attracted a lot of attention but in over a hundred years nobody has come up with a convincing explanation as to what it is.

With modern computer programs that can simulate trajectories and reconstruct the night sky thousands of years ago the researchers have established what the Planisphere tablet refers to. It is a copy of the night notebook of a Sumerian astronomer as he records the events in the sky before dawn on the 29 June 3123 BC (Julian calendar). Half the tablet records planet positions and cloud cover, the same as any other night, but the other half of the tablet records an object large enough for its shape to be noted even though it is still in space. The astronomers made an accurate note of its trajectory relative to the stars, which to an error better than one degree is consistent with an impact at Kofels.

The observation suggests the asteroid is over a kilometre in diameter and the original orbit about the Sun was an Aten type, a class of asteroid that orbit close to the earth, that is resonant with the Earth's orbit. This trajectory explains why there is no crater at Kšfels. The in coming angle was very low (six degrees) and means the asteroid clipped a mountain called Gamskogel above the town of LŠngenfeld, 11 kilometres from Kofels, and this caused the asteroid to explode before it reached its final impact point. As it travelled down the valley it became a fireball, around five kilometres in diameter (the size of the landslide). When it hit Kšfels it created enormous pressures that pulverized the rock and caused the landslide but because it was no longer a solid object it did not create a classic impact crater.

Mark Hempsell, discussing the KOfels event, said: "Another conclusion can be made from the trajectory. The back plume from the explosion (the mushroom cloud) would be bent over the Mediterranean Sea re-entering the atmosphere over the Levant, Sinai, and Northern Egypt. "The ground heating though very short would be enough to ignite any flammable material - including human hair and clothes. It is probable more people died under the plume than in the Alps due to the impact blast."

Sumerian Writing