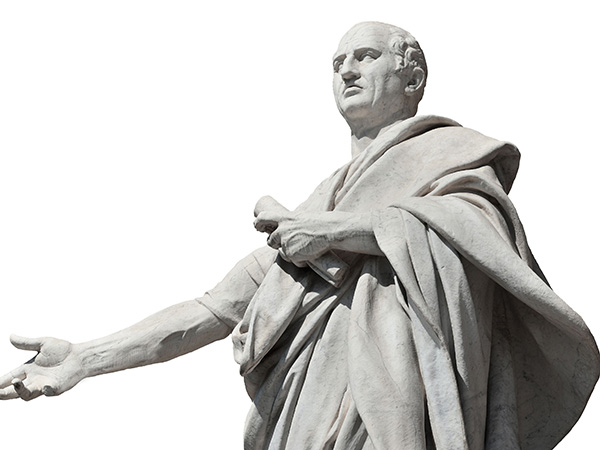

�Marcus Tullius Cicero (January 3, 106 BC - December 7, 43 BC) was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, orator, political theorist, Roman consul and constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.

He introduced the Romans to the chief schools of Greek philosophy and created a Latin philosophical vocabulary (with neologisms such as humanitas, qualitas, quantitas, and essentia) distinguishing himself as a linguist, translator, and philosopher.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited for initiating the 14th-century Renaissance. According to Polish historian Tadeusz Zielinski "Renaissance was above all things a revival of Cicero, and only after him and through him of the rest of Classical antiquity." The peak of Cicero's authority and prestige came during the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, and his impact on leading Enlightenment thinkers such as John Locke, David Hume, and Montesquieu was substantial. His works rank among the most influential in European culture, and today still constitute one of the most important bodies of primary material for the writing and revision of Roman history, especially the last days of the Roman Republic.

Though he was an accomplished orator and successful lawyer, Cicero believed his political career was his most important achievement. It was during his consulship that the Catiline conspiracy attempted the government overthrow through an attack on the city from outside forces, and Cicero suppressed the revolt by executing five conspirators without due process. During the chaotic latter half of the 1st century BC marked by civil wars and the dictatorship of Gaius Julius Caesar, Cicero championed a return to the traditional republican government. Following Julius Caesar's death Cicero became an enemy of Mark Antony in the ensuing power struggle, attacking him in a series of speeches. He was proscribed as an enemy of the state by the Second Triumvirate and subsequently murdered in 43 BC.

Cicero was born in Arpinum and killed at Formia, fleeing from political enemies. "It is no exaggeration", wrote Taylor (as cited in "References"), "to say that the most brilliant era of Roman public life was ushered in by Cicero and closed by his death - he stood at its cradle and he followed its hearse." His family, the Tullii, were one of the landed gentry in Arpinum and resented the fame and fortunes of the other great Arpinate families, the Marii. Throughout his life, the conservative Cicero loathed being compared to the then more famous Marius. The name "Cicero" is derived from cicer, the Latin word for "chickpea." Plutarch explains that the name was originally applied to one of Cicero's ancestors who had a cleft in the tip of his nose, which resembled that of a chickpea. In fact (Plutarch continues), Cicero was urged to change the theretofore-ignoble name when he entered politics, but he refused.

According to Plutarch, he was an extremely adept student, learning so well and rapidly that he attracted attention from all over Rome. He was especially fond of poetry, although he shied away from no scholarly field. In 89 BC-88 BC, Cicero served on the staffs of Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo and Lucius Cornelius Sulla as they campaigned in the Social War, though he had no taste for war. Cicero also had a love for almost everything Greek, and even stated in his will that he wanted to be buried in Greece. He found the ancient philosophers such as Plato very thought provoking.Cicero served as quaestor in western Sicily in 75 BC.

In 63 BC, Cicero became the first novus homo in more than thirty years by being elected consul. His only significant historical accomplishment during his year in office was the suppression of the Catiline conspiracy, a plot to overthrow the Roman Republic led by Lucius Sergius Catilina, a disaffected patrician. Cicero procured a senatus consultum de re publica defendenda (a declaration of martial law, also called the senatus consultum ultimum) and drove Catiline out of the city by a speech known for the harsh, almost brutal, language in which he describes the debauchery of Rome and especially Catiline. Catiline fled but left behind his 'deputies' who would start the revolution from within whilst Catiline assaulted it from without with an army recruited among Sulla's veterans in Etruria. Cicero managed to have these 'deputies' of Catiline confess their crime in front of the entire Senate, after ambushing an embassy they had sent to a Gaulish tribe.

The Senate then deliberated upon the punishment to be given to the conspirators. As it was a legislative rather than a judicial body, there were limits on its power to do so; however, martial law was in effect, and it was feared that simple house arrest or exile - the standard options - would not remove the threat to the State. At first most in the Senate spoke for the 'extreme penalty'; many were then swayed by Julius Caesar who spoke decrying the precedent it would set and argued in favor of the punishment being confined to a mode of banishment. Cato then rose in defense of the death penalty and all the Senate finally agreed on the matter. Cicero had the conspirators taken to the Tullianum, the notorious Roman prison, where they were hanged. He received the honorific "Pater Patriae" for his actions in suppressing the conspiracy, but thereafter lived in fear of trial or exile for having put Roman citizens to death without trial. He also received the first public thanksgiving for a civic accomplishment; heretofore it had been a purely military honor.

Cicero's Pro Flacco oration provides a uniquely early and clear example of anti-Semitism; in this speech, Cicero plays upon several stereotypical themes which have been echoed throughout the last two millennia. The case involved the defense of Lucius Valerius Flaccus, a Roman aristocrat, who was accused of (among other things) unlawfully confiscating Jewish funds which had been collected for the maintenance of the Temple at Jerusalem. In defense of Flaccus, Cicero made arguments regarding the public site which had been selected for the open-air tribunal: "Now let us take a look at the Jews and their mania for gold. You chose this site, chief prosecutor Laelius, and the crowd which frequents it, with an eye to this particular accusation, knowing very well that Jews with their large numbers and tendency to act as a clique are valuable supporters to have at any kind of public meeting."

In 58 BC, the populist Publius Clodius Pulcher introduced a law exiling any man who had put Roman citizens to death without trial. Although Cicero maintained that the sweeping senatus consultum ultimum granted him in 63 BC had indemnified him against legal penalty, he nevertheless appeared ragged in public and began to beg for support from the people. Seeing that he could not go out in public without being lambasted by Clodius's heavies, he dedicated a statue to Minerva in the Forum and left Italy for a year and spent his quasi-exile setting his speeches to paper.

In letters to his friend Atticus, Cicero maintained that the Senate was jealous of his accomplishments which was why they did not save him from exile.Cicero returned after over a dozen months from his exile to a cheering crowd, much in the manner of Demosthenes, which the historian Appian pointed out. During the 50s, Cicero supported the populist Milo to use as a spear head against Clodius, who continued to use his popular support to establish terror in the streets.

During the mid-50s, Clodius was killed by Milo's gladiators on the Via Appia. Cicero defended Milo on counts of murder from the relatives of Clodius, yet failed. Despite this failure, Cicero's Pro Milone was considered by some as his ultimate masterpiece. Cicero argued that Milo had no reason to kill Clodius and had all to gain from his living, pointing out that Milo had no idea that he would encounter Clodius on the Via Appia.

The prosecution, however, pointed out that Milo had freed his slaves who were with him during the bout with Clodius so that they could not testify against him in court on charges that he had ordered the killing of Clodius. Cicero rejected this, saying that Milo's slaves had defended him honorably and deserved to be free, seeing as how they had saved their master from an attack by Clodius.

Milo fled into exile and continued to live in Massilia until he returned to stir up further trouble during the Civil War.As the struggle between Pompey and Julius Caesar grew more intense in 50 BC, Cicero favored Pompey but tried to avoid turning Caesar into a permanent enemy. When Caesar invaded Italy in 49 BC, Cicero fled Rome. Caesar attempted vainly to convince him to return, and in June of that year Cicero slipped out of Italy and traveled to Dyrrachium (Epidamnos).

In 48 BC, Cicero was with the Pompeians at the camp of Pharsalus and quarreled with many of the Republican commanders, including a son of Pompey. They in turn disgusted him by their bloody attitudes. He returned to Rome, however, after Caesar's victory at Pharsalus.

In a letter to Varro on April 20, 46 BC, Cicero indicated what he saw as his role under the dictatorship of Caesar: "I advise you to do what I am advising myself Ð avoid being seen, even if we cannot avoid being talked about... If our voices are no longer heard in the Senate and in the Forum, let us follow the example of the ancient sages and serve our country through our writings, concentrating on questions of ethics and constitutional law."

In February 45 BC, Cicero's daughter Tullia died. He never entirely recovered from this shock.

Cicero was taken completely by surprise when Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March 44 BC. In a letter to the conspirator Trebonius, Cicero expressed a wish of having been "...invited to that superb banquet..." Cicero became a popular leader during the instability and was disgusted with Mark Antony, Caesar's former Master of the Horse who was hoping to take revenge upon the murderers of Caesar by first having him not outlawed a tyrant so that the Caesarians could have lawful support, in exchange for amnesty for the assassins which the Senate agreed to.

Cicero and Antony, Caesar's subordinate, became the leading men in Rome; Cicero as spokesman for the Senate, and Antony as consul and as executor of Caesar's will. But the two men had never been on friendly terms, and their relationship worsened after Cicero made it clear he felt Antony to be taking unfair liberties in interpreting Caesar's wishes and intentions. When Octavian, Caesar's heir, arrived in Italy in April, Cicero formed a plan to play him against Antony. In September he began attacking Antony in a series of speeches he called the Philippics.

Praising Octavian to the skies, he labeled him a "God-Sent Child" and said he only desired honor and that he would not make the same mistake as his father. Meanwhile, his attacks on Antony, whom he called a "sheep," rallied the Senate in firm opposition to Antony.

During this time, Cicero became an unrivaled popular leader and, according to the historian Appian, "had the power any popular leader could possibly have." He was at the height of his fame. As popular leader, Cicero heavily fined the supporters of Antony for petty charges and had volunteers forge arms for the Republicans. It turned out to be so insulting that a right hand man of Antony was preparing to march on Rome to arrest Cicero.

Cicero fled the city and the plan was abandoned. Appian is the only one to give this tale of a march on Rome for the arrest of Cicero.Cicero supported Marcus Junius Brutus as governor of Cisalpine Gaul (Gallia Cisalpina) and urged the Senate to name Antony an enemy of the state. One tribune, a certain Salvius, delayed these proceedings and was "reviled," as Appian put it, by Cicero and his party. The speech of Lucius Piso, Caesar's father-in-law, delayed proceedings against Antony.

Antony was later declared an enemy of the state when he refused to lift the siege of Mutina, which was in the hands of one of Caesar's assassins, Decimus Brutus, who also was named a second son in Caesar's will. Cicero described his position in a letter to Cassius, one of Caesar's assassins, that same September: "I am pleased that you like my motion in the Senate and the speech accompanying it... Antony is a madman, corrupt and much worse than Caesar - whom you declared the worst of evil men when you killed him.

Antony wants to start a bloodbath..."Cicero's plan to drive out Octavian and Antony failed, however. The two reconciled and allied with Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate after the successive battles of Mutina. Immediately after legislating their alliance into official existence for a five-year term with consular imperium, the Triumviri began proscribing their enemies and potential rivals. Cicero and his younger brother Quintus Tullius Cicero, formerly one of Caesar's legates, and all of their contacts and support were numbered among the enemies of the state.

Antony hunted for Cicero most viciously among the proscribed. Many men fell bravely, with many stories of bravery and virtue according to historical accounts. One victim turned out to be the tribune Salvius, who, after siding with Antony, moved his support directly and fully to Cicero. Salvius held a dinner party for his friends because he knew he would not be around for long and wished to have one last gathering to say goodbye.

The legionaries burst into the party and beheaded Salvius in front of his friends.Cicero was viewed with pity by many, and many claimed not to have seen him. He fled, but was caught at one of his villas after going to retrieve money. He fled by the coast of the nearby villa.

When the executioners arrived, his slaves said they did not see him, yet a dependent of Clodius said otherwise. His last words were said to have been "there is nothing proper about what you are doing, soldier, but do try to kill me properly."

He was decapitated by his pursuers on December 7, 43 BC; his head and hands were displayed on the Rostra in the Forum Romanum according to the tradition of Marius and Sulla, both of whom had displayed the heads of their enemies in the Forum.

He was the only victim of the Triumvirate's proscriptions to have been so displayed after death. According to Plutarch, Antony's wife Fulvia took Cicero's head, pulled out his tongue, and jabbed the tongue repeatedly with her hatpin, taking a final revenge against Cicero's power of speech.

Of his speeches, eighty-eight were recorded, but only fifty-eight survive.

ANCIENT AND LOST CIVILIZATIONS