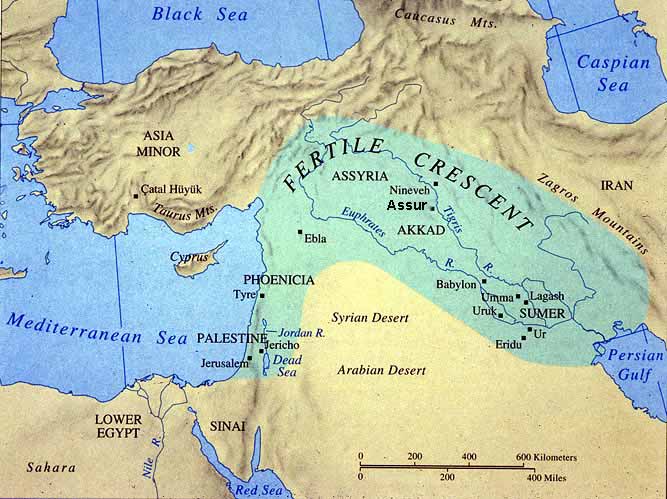

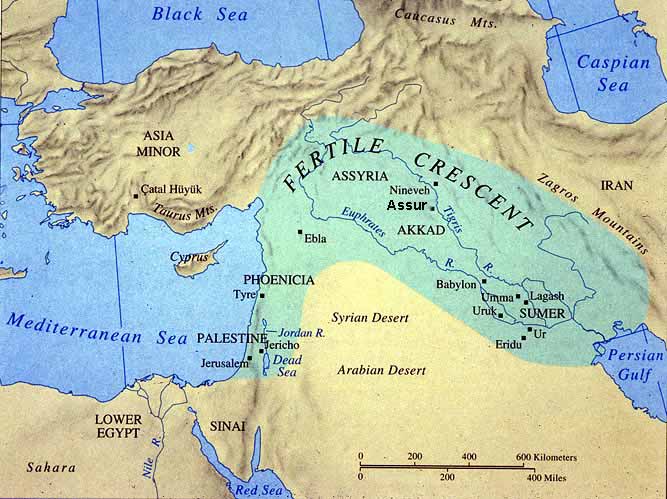

Assyria in earliest historical times referred to a region on the Upper Tigris river, named for its original capital, the ancient city of Ashur. Later, as a nation and Empire, it also came to include roughly the northern half of Mesopotamia (the southern half being Babylonia). Assyria proper was located in a mountainous region, extending along the Tigris as far as the high Gordiaean or Carduchian mountain range of Armenia, sometimes called the "Mountains of Ashur".

Of the early history of the kingdom of Assyria, little is positively known. According to some Judeo-Christian traditions, the city of Ashur was founded by Ashur the son of Shem, who was deified by later generations as the city's patron god. Besides Ashur, the other three royal Assyrian cities were Calah (Nimrud), Khorsabad, and Nineveh.

This region seems to have been ruled from Sumer, Akkad, and northern Babylonia in its earliest stages, being part of Sargon the Great's empire. Destroyed by barbarians in the Gutian period, it was rebuilt, and ended up being governed as part of the Empire of the 3rd dynasty of Ur. Assyria as an independent kingdom was perhaps founded ca. 1900 BC by Bel-kap-kapu.

Basic to the central region of Assyria was farming, fed by both the Tigris river and water from the Armenian mountains in the north, and the Zagros mountains in the east. With the expansion of Assyria, more land brought other economies, like mining and forestry. It is believed that Assyria's civilization resulted from the immigration of an unknown people into the area around 6000 BCE. This was followed by Semitic immigration about 3 millennia later. Life was confined to small villages, and there was an intricate system of irrigation that fed the agriculture. There were few larger cities, and these served as trade and craft centers. Assyria had some slaves, but these played only a small part in the economy.

Assyrian architecture used mud bricks, and occasionally stone. Houses and buildings never exceeded one story and had flat roofs. While most houses were modest, palaces and temples could cover large areas inside the cities.

Sculptures and wall carvings were another central part of Assyrian culture, and showed high skill in craftsmanship.

Document cylinder seals became an art form in itself, as intricate patterns and shapes were given to these.

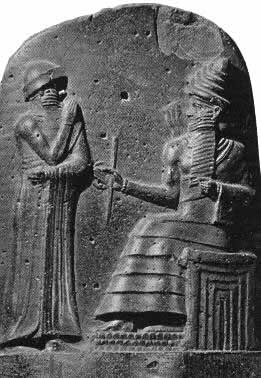

Ancient astronaut theorists, interpret this relief as a spaceman breathing through some sort of apparatus. Others see it differently.

From the royal palace of Nimrud: Assyrian swimmers: 2,900-year-old carving of soldiers using inflatable goat skins to cross a river Live Science - June 23, 2025

This carved relief from Nimrud, a major city of the ancient Assyrian Empire in present-day Iraq, regularly drifts around the internet as purported evidence for scuba diving nearly 3,000 years ago. But the wall panel actually depicts an army crossing a river, and soldiers are navigating the waves with the help of ancient flotation devices.

The gypsum panel is one of several excavated in the 1840s from the Northwest Palace, which was built on the Tigris River around 865 B.C. on the orders of King Ashurnasirpal II. Originally located around the interior walls of the throne room and royal apartments, the carved panels depict the king leading a military campaign, engaging in rituals and hunting animals. This panel fragment, which is in the collection of The British Museum, shows several men and horses crossing a river. The horses are swimming, pulled on leads by cavalry soldiers. One soldier is free-swimming, one is rowing a small boat, and two are using goat-skin bags that the soldiers are inflating to stay afloat.

A cuneiform inscription running across the top of the panel traces the king's lineage and describes his key accomplishments. The two-dimensionality of the perspective - in which the figures appear complete and not half-submerged - is typical in Assyrian art.

Animal skin or bladder floats appear several times in the Nimrud wall panels, and they were likely made from goats or pigs. The floats were used to help keep a soldier's weapons dry and to allow an army to sneak up on an enemy. Ashurnasirpal II was known for his military prowess as well as his brutality, and his innovative tactics - including the goat-skin floats - helped him expand his empire considerably in the ninth century B.C.

While it's interesting to ponder how much of the world the Assyrian army might have conquered if they'd had scuba gear, the humble goat skin still represents a key invention that helped them maintain power in Mesopotamia for centuries, until the empire fell around 600 B.C.

Ancient Assyrian capital that's been abandoned for 2,700 years revealed in new magnetic survey

Live Science - December 22, 2024

A new magnetic survey of the ancient Assyrian capital of Khorsabad has revealed several structures, including a villa, buried underground. Archaeologists in northern Iraq have discovered the remains of a massive villa, royal gardens and other structures buried deep underground at what was once the ancient Assyrian capital of Khorsabad, a new magnetic survey reveals. The international team of researchers used a magnetometer in unusually taxing conditions to detect the 2,700-year-old city's water gate, possible palace gardens and five large buildings including a villa with 127 rooms that is twice the size of the White House. The previously undiscovered structures challenge the notion that Khorsabad was never developed beyond a palace complex in the eighth century B.C., according to an American Geophysical Union (AGU)

Mysterious Code in Ancient Assyrian Temples Can Finally Be Explained

Science Alert - May 20, 2024

An ancient pictorial code that has intrigued experts for over a century may have been interpreted fully for the first time, giving us further insight into the mighty Assyrian empire that stretched across large parts of the Middle East from the 14th to 7th centuries BCE.

In particular, these symbols relate to King Sargon II, who ruled from 721-704 BCE. In their short form, they comprise a lion, a fig tree, and a plough. In their longer form, there are five symbols in sequence: a bird and a bull after the lion, then the tree and the plough.

These images appear in several places in temples in Dur-Sarrukin which was briefly Assyria's capital. The buried ruins of the ancient city were excavated during the 19th and 20th centuries. But the meaning of the images - whether they represent gods, supernatural forces, the king's authority, or an attempt at Egyptian hieroglyphs has long been debated.

This region of the world, which includes present-day Iraq and parts of Iran, Turkey and Syria, is often referred to as the 'cradle of civilization'. It's where cities and empires were born, and its story is a huge part of human history.

Assyrians have used two languages throughout their history: ancient Assyrian (Akkadian), and Modern Assyrian (neo-syriac). The Arameans, would eventually see their language, Aramaic, supplant Ancient Assyrian because of the technological breakthrough in writing.

Aramaic was made the second official language of the Assyrian empire in 752 B.C. Although Assyrians switched to Aramaic, it was not wholesale transplantation. The brand of Aramaic that Assyrians spoke was, and is, heavily infused with Akkadian words, so much so that scholars refer to it as Assyrian Aramaic.

Among the finest cultural achievements of Assyria was literature, which initially used a cuneiform alphabet from the Babylonians written on clay tablets until 750 BC. Later an Aramaic script written on parchment, papyrus, or leather predominated. The literature dealt with a number of subjects like legal issues, medicine and history.

The Assyrian culture had dramatic growth in science and mathematics. This can be in part explained by the Assyrian obsession with war and invasion. Among the great mathematical inventions of the Assyrians were the division of the circle into 360 degrees and were among the first to invent longitude and latitude in geographical navigation. They also developed a sophisticated medical science which greatly influenced medical science as far away as Greece.

There is ongoing discussion among academics over the nature of the Nimrud lens, a piece of rock crystal unearthed by John Layard in 1850, in the Nimrud palace complex in northern Iraq. A small minority believe that it is evidence for the existence of ancient Assyrian telescopes, which could explain the great accuracy of Assyrian astronomy.

The city-state of Ashur had extensive contact with cities on the Anatolian plateau. The Assyrians established "merchant colonies" in Cappadocia, e.g., at Kanesh (modern Kultepe) circa 1920 -1840 BC and 1798 -1740 BC. These colonies, called 'Karum', the Akkadian word for 'port', were attached to Anatolian cities, but physically separate, and had special tax status. Trade consisted of metal - lead and tin and textiles that were traded for precious metals in Anatolia.

The city of Ashur was conquered by Shamshi-Adad I (1813-1791 BC) in the expansion of Amorite tribes from the Khabur delta. He put his son Ishme-Dagan on the throne of nearby Ekallatum, and allowed trade to continue. Only after the death of Shamshi-Adad and the fall of his sons, did Hammurabi of Babylon conquer Ashur.

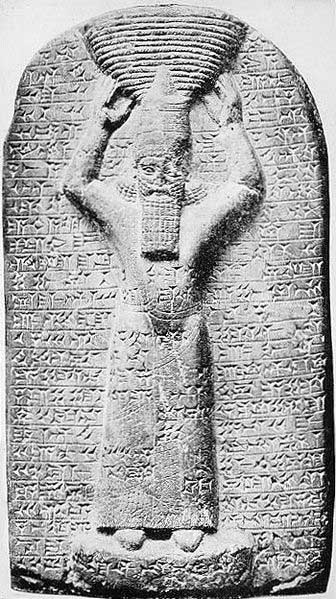

Hammurabi

Sixth King of the First Babylonian dynasty of the Amorite Tribe

With Hammurabi, the various karum in Anatolia ceased trade activity, probably because the goods of Assyria were now being traded with the Babylonians' partners.

In the 15th century BC, Saushtatar, king of "Hanilgalbat" (Hurrians of Mitanni), sacked Ashur and made Assyria a vassal. Assyria paid tribute to Hanilgalbat until Mitanni power collapsed from Hittite pressure, enabling Ashur-uballit I (1365 BC-1330 BC), to again make Assyria an independent and conquering power.

Hanilgalbat was finally conquered under Adad-nirari I, who described himself as a "Great-King" (Sharru rabu) in letters to the Hittite rulers.

Adad-nirari I's successor, Shalmaneser I, made Calah his capital, and followed up on expansion to the northwest, mainly at the expense of the Hittites, reaching as far as Carchemish.

His son and successor, Tukulti-Ninurta, deposed Kadashman-Buriash of Babylon and ruled there himself, as king for seven years. Following this, Babylon revolted against Tukulti-Ninurta, and later even made Assyria tributary during the reigns of the Babylonian kings Melishipak II and Marduk-apal-iddin I, another weak period for Assyria.

Assyrian Officials

The Assyrian state was forged in the crucible of war, invasion, and conquest. The upper, land-holding classes consisted almost entirely of military commanders who grew wealthy from the spoils taken in war. The army was the largest standing army ever seen in the Middle East or Mediterranean. The exigencies of war excited technological innovation which made the Assyrians almost unbeatable: iron swords, lances, metal armor, and battering rams made them a fearsome foe in battle.

As the Hittite empire collapsed from onslaught of the Phrygians (called Mushki in Assyrian annals), Babylon and Assyria began to vie for Amorite regions, formerly under firm Hittite control. The Assyrian king Ashur-resh-ishi defeated Nebuchadnezzar I of Babylon in a battle, when their forces encountered one another in this region.

In 1120 BC, Ashur-resh-ishi's son, Tiglath-Pileser I crossed the Euphrates, capturing Carchemish, defeated the Mushki and the remnants of the Hittites - even claiming to reach the Black Sea - and advanced to the Mediterranean, subjecting Phoenicia. He also marched into Babylon twice, assuming the old title "King of Sumer and Akkad", although he was unable to depose the actual Babylonian king on these occasions. He may be regarded as the founder of the first Assyrian empire.

After Tiglath-Pileser I, the Assyrians were in decline for nearly two centuries, a time of weak and ineffective rulers, wars with neighboring Urartu, and encroachments by Aramaean nomads. This long period of weakness ended with the accession in 911 BC of Adad-nirari II. He brought the areas still nominally under Assyrian vassalage firmly under subjection, deporting populations in the north to far-off places. Apart from pushing the boundary with Babylonia slightly southward, he did not engage in actual expansion, and the borders of the empire he consolidated reached only as far west as the Khabur. He was succeeded by Tukulti-Ninurta II, who made some gains in the north during his short reign.

The next king, Ashurnasirpal II (883 BC-858 BC), embarked on a vast program of merciless expansion, first terrorizing the peoples to the north as far as Nairi, then subjecting the Aramaeans between the Khabur and the Euphrates. His harshness prompted a revolt that was crushed decisively in a pitched, two-day battle. Following this victory, he advanced without opposition as far as the Mediterranean and exacted tribute from Phoenicia. Unlike any before, the Assyrians began boasting in their ruthlessness around this time. Ashurnasirpal II also moved his capital to the city of Kalhu (Nimrud).

Ashurnasirpal's son, Shalmaneser III (858 BC-823 BC), fought against Urartu, and in the reign of Ahab, king of Israel, he marched an army against an alliance of the Syrian states (a rare occasion in near-eastern history of an alliance between the Israeli state and the Aramaic Kingdom), whose allied army he encountered at Karkar in (854 BC). Despite Shalmaneser's description of 'vanquishing the opposition', it seems that the battle ended in a deadlock, as the Assyrian forces were withdrawn soon afterwards. Shalmaneser retook Carchemish in 849 BC, and in 841 BC marched an army against Hazael, King of Damascus, besieging and taking that city. He also brought under tribute Jehu of Israel, Tyre, and Sidon. His black obelisk, discovered at Kalhu, records many military exploits of his reign.

In the following century, Assyria again experienced a relative decline, owing to weaker rulers (including the Queen Semiramis) and a resurgence in expansion by Urartu. The notable exception was Adad-nirari III (810 BC-782 BC), who brought Syria under tribute as far south as Edom and advanced against the Medes, perhaps even penetrating to the Caspian Sea.

In 745 BC, the crown was seized by a military adventurer called Pul, who assumed the name of Tiglath-Pileser III. After subjecting Babylon to tribute and severely punishing Urartu, he directed his armies into Syria, which had regained its independence.

He took Arpad near Aleppo in 740 BC after a siege of three years, and reduced Hamath. Azariah (Uzziah) had been an ally of the king of Hamath, and thus was compelled by Tiglath-Pileser to do him homage and pay yearly tribute.In 738 BC, in the reign of Menahem, king of Israel, Tiglath-Pileser III occupied Philistia and invaded Israel, imposing on it a heavy tribute (2 Kings 15:19). Ahaz, king of Judah, engaged in a war against Israel and Syria, appealed for help to this Assyrian king by means of a present of gold and silver (2 Kings 16:8); he accordingly "marched against Damascus, defeated and put Rezin to death, and besieged the city itself."

Leaving part of his army to continue the siege, he advanced, ravaging with fire and sword the province east of the Jordan, Philistia, and Samaria; and in 732 BC took Damascus, deporting its inhabitants to Assyria. In 729 BC, he had himself crowned as "King Pul of Babylon".

Tiglath-Pileser III died in 727 BC, and was succeeded by Shalmaneser V, who reorganized the Empire into provinces, replacing the troublesome vassal kings with Assyrian governors. However, King Hoshea of Israel suspended paying tribute, and allied himself with Egypt against Assyria in 725 BC. This led Shalmaneser to invade Syria (2 Kings 17:5) and besiege Samaria (capital city of Israel) for three years.

Shalmaneser V was deposed in 722 BC in favour of Sargon, the Tartan (commander-in-chief of the army), who then quickly took Samaria, carrying 27,000 people away into captivity into the Israelite Diaspora, and effectively ending the northern Kingdom of Israel. (2 Kings 17:1-6, 24; 18:7, 9).

He also overran Judah, and took Jerusalem (Isa. 10:6, 12, 22, 24, 34). In 721 BC, Babylon threw off the rule of the Assyrians, under the powerful Chaldean prince Merodach-baladan (2 Kings 20:12), and Sargon, unable to contain the revolt, turned his attention again to Syria, Urartu, and the Medes, penetrating the Iranian Plateau as far as Mt. Bikni and building several fortresses, before returning in 710 BC and retaking Babylon.

Sargon also built a new capital at Dur Sharrukin ("Sargon's City") near Nineveh, with all the tribute Assyria had collected from various nations.In 705 BC, Sargon was slain while fighting the Cimmerians, and was succeeded by his son Sennacherib (2 Kings 18:13; 19:37; Isa. 7:17, 18), who moved the capital to Nineveh and made the deported peoples work on improving Nineveh's system of irrigation canals.

In 701 BC, Hezekiah of Judah formed an alliance with Egypt against Assyria, so Sennacherib accordingly marched toward Jerusalem, destroying 46 villages in his path.

This is graphically described in Isaiah 10; exactly what happened next is unclear (the Bible says an Angel of the Lord smote the Assyrian army at Jerusalem; Herodotus says they were destroyed by a plague of field mice at Egypt; modern historians suspect Plague in both instances); however what is certain, is that the besieging army was somehow decimated, and Sennacherib failed to capture Jerusalem.

In 689 BC, Babylonia again revolted, but Sennacherib responded swiftly by opening the canals around Babylon and flooding the outside of the city until it became a swamp, resulting in its destruction, and its inhabitants were scattered. In 681 BC, Sennacherib was murdered, most likely by one of his sons.

Sennacherib was succeeded by his son Esarhaddon (Ashur-aha-iddina), who had been governor of Babylonia under his father. As king, he immediately had Babylon rebuilt, and made it his capital.

Defeating the Cimmerians and Medes (again penetrating to Mt. Bikni), but unable to maintain order in these areas, he turned his attention westward to Phoenicia - now allying itself with Egypt against him - and sacked Sidon in 677 BC.

He also captured Manasseh of Judah and kept him prisoner for some time in Babylon (2 Kings 19:37; Isa. 37:38). Having had enough of Egyptian meddling, he next invaded that country in 674 BC, conquering it all by 670 BC.

Assyria was also at war with Urartu and Dilmun (probably modern Qatar) at this time. This was Assyria's greatest territorial extent.

However, the Assyrian governors Esarhaddon had appointed over Egypt were obliged to flee the restive populace, and while leading another army to pacify them, Esarhaddon died suddenly, in 669 BC.Assur-bani-pal or Ashurbanipal (Ashurbanapli, Asnappar), the son of Esarhaddon, succeeded him.

He continued to campaign in Egypt, when not distracted by pressures from the Medes to the east, and Cimmerians to the north of Assyria.

Unable to contain Egypt, he installed Psammetichus as a vassal king in 663 BC, but by 652 BC, this vassal king was strong enough to declare outright independence from Assyria with impunity, especially as Ashurbanipal's brother, Shamash-shum-ukin, governor of Babylon, began a civil war in that year that lasted until 648 BC, when Babylon was sacked and the brother set fire to the palace, killing himself. Elam was completely devastated in 646 BC and 640 BC.

Ashurbanipal had promoted art and culture, and had a vast library of cuneiform tablets at Nineveh, but upon his death in 627 BC, the Assyrian Empire began to disintegrate rapidly. Babylonia became independent; their king Nabopolassar, along with Cyaxares of Media, destroyed Nineveh in 612 BC, and Assyria fell. A general called Ashur-uballit II, with military support from the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II, held out as a remnant of Assyrian power at Harran until 609 BC, after which Assyria ceased to exist as an independent nation. However, the Assyrian people have managed to keep their identity, and still exist as a distinct ethnic group, mainly in northern Iraq, where they are distinguished from their Arab, Kurdish, and Turkmen neighbors by their traditions, politics, Christian religion, and Aramaic dialect.

The list of Assyrian kings is compiled from the Assyrian King List, an ancient kingdom in northern Mesopotamia (modern northern Iraq) with information added from recent archaeological findings. The Assyrian King List includes regnal lengths that appear to have been based on now lost limmu lists (which list the names of eponymous officials for each year). These regnal lengths accord well with Hittite, Babylonian and ancient Egyptian king lists and with the archaeological record, and are considered reliable for the age.

Prior to the discovery of cuneiform tablets listing ancient Assyrian kings, scholars before the 19th century only had access to two complete Assyrian King Lists, one found in Eusebius of Caesarea's Chronicle (c. 325 AD), of which two editions exist and secondly a list found in the Excerpta Latina Barbari.

An incomplete list of 16 Assyrian kings was also discovered in the literature of Sextus Julius Africanus. Other very fragmentary Assyrian king lists have come down to us written by the Greeks and Romans such as Ctesias of Cnidus (c. 400 BC) and the Roman authors Castor of Rhodes (1st century BC) and Cephalion (1st century AD).

Unlike the cuneiform tablets, the "other" Assyrian King Lists are not considered to be wholly factual (since they contain some mythological figures) and thus are only considered to contain minor historical truths. Some scholars argue further that they are either entire fabrications or fiction.

There are three extant cuneiform tablet versions of the King List, and two fragments. They date to the early first millennium BC - the oldest, List A (8th century BC) stopping at Tiglath-Pileser II (ca. 967–935 BC) and the youngest, List C, at Shalmaneser V (727–722 BC). Assyriologists believe the list was originally compiled to link Shamshi-Adad I (fl. ca. 1700 BC (short)), an Amorite who had conquered Assur, to the native rulers of the land of Assur. Scribes then copied the List and added to it over time.

Tiglath-Pileser III (745-727 BC)

Tiglath-Pileser III is widely regarded as the founder of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. He seized the Assyrian throne during a civil war and killed the royal family. He made sweeping changes to the Assyrian government, considerably improving its efficiency and security. Assyrian forces became a standing army. Tiglath-Pileser III subjected Babylonia to tribute, severely punished Urartu (Armenia), and defeated the Medes and the Hittites. He reconquered Syria (destroying Damascus) and the Mediterranean seaports of Phoenicia. Tiglath-Pileser III also occupied Philistia and Israel. Later in his reign, Tiglath-Pileser III assumed total control of Babylonia. Tiglath-Pileser III discouraged revolts against Assyrian rule, with the use of forced deportations of thousands of people all over the empire. He is considered to be one of the most successful military commanders in world history, conquering most of the world known to the Assyrians before his death.

Sumerian Pantheon - Annunaki