�The Antikythera Mechanism is believed to be an ancient mechanical analog computer (as opposed to most computers today which are digital computers) designed to calculate astronomical positions. It was discovered in the Antikythera wreck off the Greek island of Antikythera, between Kythera and Crete, and has been dated to about 150-100 BC. It is especially notable for being a technological artifact with no known predecessor or successor; other machines using technology of such complexity would not appear until the 18th century.

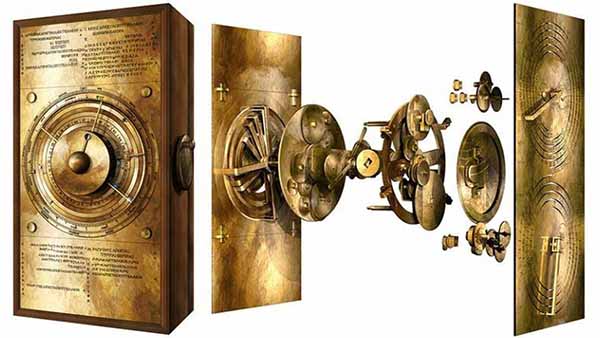

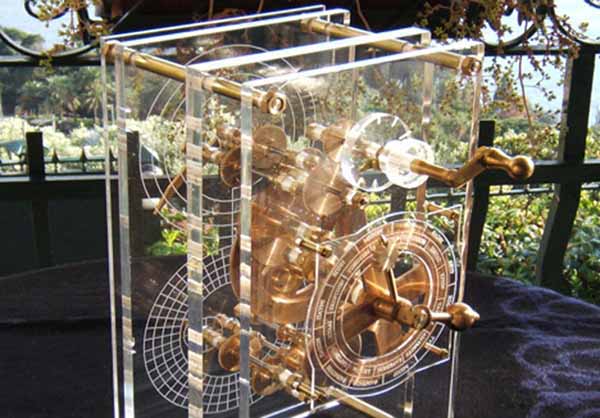

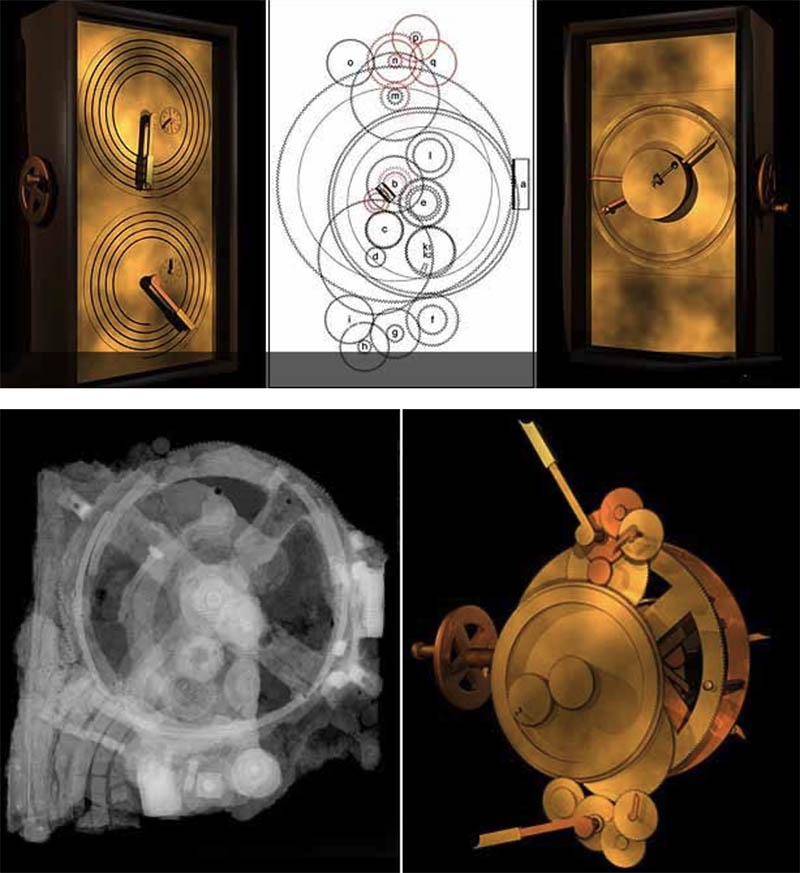

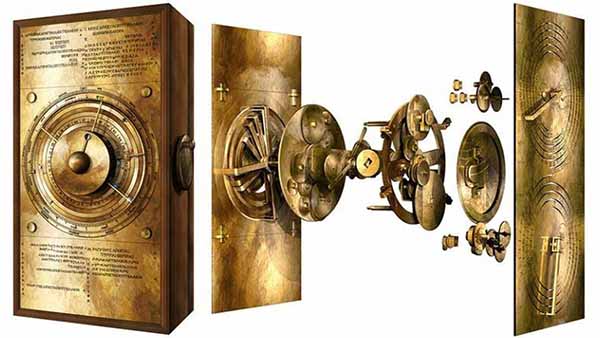

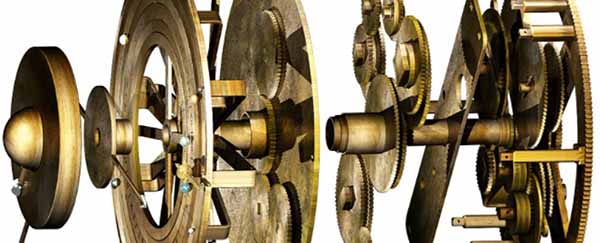

The mechanism was housed in a wooden box approximately 340 x 180 x 90 mm in size and comprised 30 bronze gears (although more could have been lost). The largest gear, clearly visible in fragment A, was approximately 140 mm in diameter and probably had either 223 or 224 teeth. The mechanism's remains were found as 82 separate fragments of which only seven contain any gears or significant inscriptions.

The Antikythera Mechanismis generally referred to as the first known analogue computer. The quality and complexity of the mechanism's manufacture suggests that it must have had undiscovered predecessors made during the Hellenistic period. Its construction relied on theories of astronomy and mathematics developed by Greek astronomers during the second century BC, and it is estimated to have been built in the late second century BC or the early first century BC.

In 1974, Derek de Solla Price concluded from gear settings and inscriptions on the mechanism's faces that it was made about 87 BC and lost only a few years later. Jacques Cousteau and associates visited the wreck in 1976 and recovered coins dated between 76 and 67 BC. The mechanism's advanced state of corrosion has made it impossible to perform an accurate compositional analysis, but it is believed that the device was made of a low-tin bronze alloy (of approximately 95% copper, 5% tin).[44] Its instructions were composed in Koine Greek.[

In 2008, continued research by the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project suggested that the concept for the mechanism may have originated in the colonies of Corinth, since they identified the calendar on the Metonic Spiral as coming from Corinth or one of its colonies in northwest Greece or Sicily. Syracuse was a colony of Corinth and the home of Archimedes, and the Antikythera Mechanism Research project argued in 2008 that it might imply a connection with the school of Archimedes. However, it was demonstrated in 2017 that the calendar on the Metonic Spiral is indeed of the Corinthian type but cannot be that of Syracuse.

Another theory suggests that coins found by Jacques Cousteau at the wreck site in the 1970s date to the time of the device's construction, and posits that its origin may have been from the ancient Greek city of Pergamon, home of the Library of Pergamum. With its many scrolls of art and science, it was second in importance only to the Library of Alexandria during the Hellenistic period.

The ship carrying the device also contained vases in the Rhodian style, leading to a hypothesis that it was constructed at an academy founded by Stoic philosopher Posidonius on that Greek island. Rhodes was a busy trading port in antiquity and a centre of astronomy and mechanical engineering, home to astronomer Hipparchus, who was active from about 140 BC to 120 BC.

The mechanism uses Hipparchus' theory for the motion of the Moon, which suggests the possibility that he may have designed it or at least worked on it. In addition, it has recently been argued that the astronomical events on the Parapegma of the Antikythera mechanism work best for latitudes in the range of 33.3-37.0 degrees north; the island of Rhodes is located between the latitudes of 35.85 and 36.50 degrees north.

In 2014, a study by Carman and Evans argued for a new dating of approximately 200 BC based on identifying the start-up date on the Saros Dial as the astronomical lunar month that began shortly after the new moon of 28 April 205 BC. Moreover, according to Carman and Evans, the Babylonian arithmetic style of prediction fits much better with the device's predictive models than the traditional Greek trigonometric style.

A study by Paul Iversen published in 2017 reasons that the prototype for the device was indeed from Rhodes, but that this particular model was modified for a client from Epirus in northwestern Greece; Iversen argues that it was probably constructed no earlier than a generation before the shipwreck, a date supported also by Jones.

Further dives were undertaken in 2014, with plans to continue in 2015, in the hope of discovering more of the mechanism.

A five-year program of investigations began in 2014 and ended in October 2019, with a new five-year session started in May 2020.

Captain Dimitrios Kontos and a crew of sponge divers from Symi island discovered the Antikythera shipwreck during the spring of 1900, and recovered artefacts during the first expedition with the Hellenic Royal Navy, in 1900Ð01. This wreck of a Roman cargo ship was found at a depth of 45 metres (148 ft) off Point Glyphadia on the Greek island of Antikythera. The team retrieved numerous large artifacts, including bronze and marble statues, pottery, unique glassware, jewellery, coins, and the mechanism. The mechanism was retrieved from the wreckage in 1901, most probably in July of that year. It is not known how the mechanism came to be on the cargo ship, but it has been suggested that it was being taken from Rhodes to Rome, together with other looted treasure, to support a triumphal parade being staged by Julius Caesar.

All of the items retrieved from the wreckage were transferred to the National Museum of Archaeology in Athens for storage and analysis. The mechanism appeared at the time to be little more than a lump of corroded bronze and wood; it went unnoticed for two years, while museum staff worked on piecing together more obvious treasures, such as the statues.

On 17 May 1902, archaeologist Valerios Stais found that one of the pieces of rock had a gear wheel embedded in it. He initially believed that it was an astronomical clock, but most scholars considered the device to be prochronistic, too complex to have been constructed during the same period as the other pieces that had been discovered. Investigations into the object were dropped until British science historian and Yale University professor Derek J. de Solla Price became interested in it in 1951.

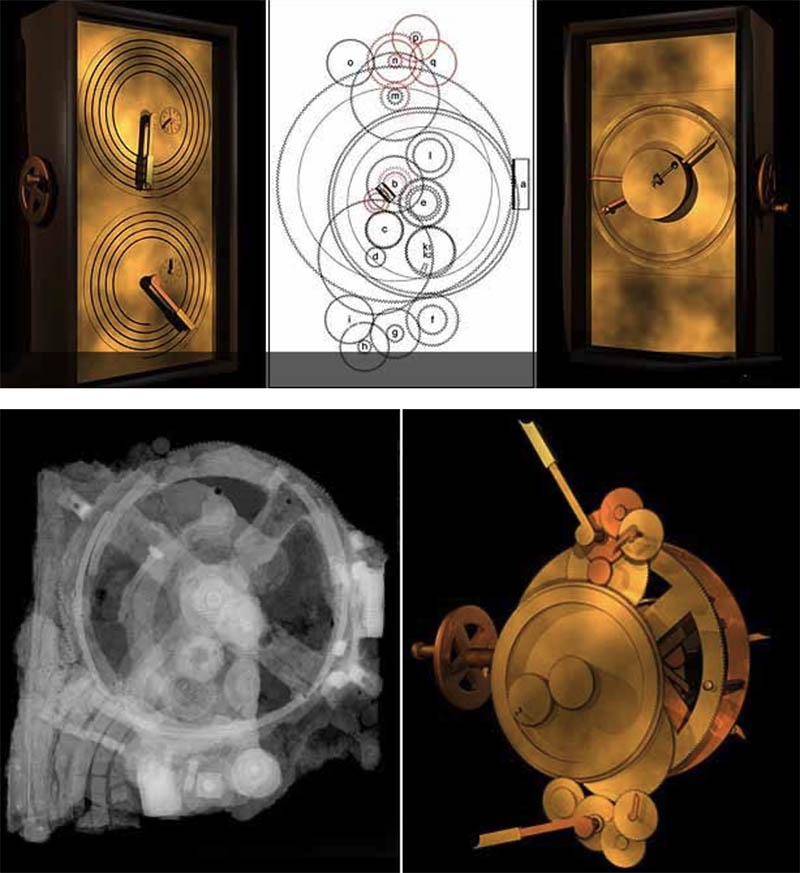

In 1971, Price and Greek nuclear physicist Charalampos Karakalos made X-ray and gamma-ray images of the 82 fragments. Price published an extensive 70-page paper on their findings in 1974.

Two other searches for items at the Antikythera wreck site in 2012 and 2015 have yielded a number of fascinating art objects and a second ship which may or may not be connected with the treasure ship on which the Mechanism was found.

Also found was a bronze disc, embellished with the image of a bull. The disc has four "ears" which have holes in them, and it was thought by some that it may have been part of the Antikythera Mechanism itself, as a "cog wheel". However, there appears to be little evidence that it was part of the Mechanism; it is more likely that the disc was a bronze decoration on a piece of furniture.

The original mechanism apparently came out of the Mediterranean as a single encrusted piece. Soon afterward it fractured into three major pieces. Other small pieces have broken off in the interim from cleaning and handling, and still others were found on the sea floor by the Cousteau expedition. Other fragments may still be in storage, undiscovered since their initial recovery; Fragment F was discovered in that way in 2005. Of the 82 known fragments, seven are mechanically significant and contain the majority of the mechanism and inscriptions. There are also 16 smaller parts that contain fractional and incomplete inscriptions

The device, housed in the remains of a 34 cm x 18 cm x 9 cm [13.4 in x 7.1 in x .5 in] wooden box, was found as one lump, later separated into three main fragments which are now divided into 82 separate fragments after conservation efforts. Four of these fragments contain gears, while inscriptions are found on many others. The largest gear is approximately 13 centimetres (5.1 in) in diameter and originally had 223 teeth.

It is a complex clockwork mechanism composed of at least 30 meshing bronze gears. In 2008, a team led by Mike Edmunds and Tony Freeth at Cardiff University used modern computer x-ray tomography and high resolution surface scanning to image inside fragments of the crust-encased Mechanism and read the faintest inscriptions that once covered the outer casing of the machine.

Detailed imaging of the mechanism suggests that it had 37 gear wheels enabling it to follow the movements of the Moon and the Sun through the zodiac, to predict eclipses and to model the irregular orbit of the Moon, where the Moon's velocity is higher in its perigee than in its apogee. This motion was studied in the 2nd century BC by astronomer Hipparchus of Rhodes, and it is speculated that he may have been consulted in the machine's construction.

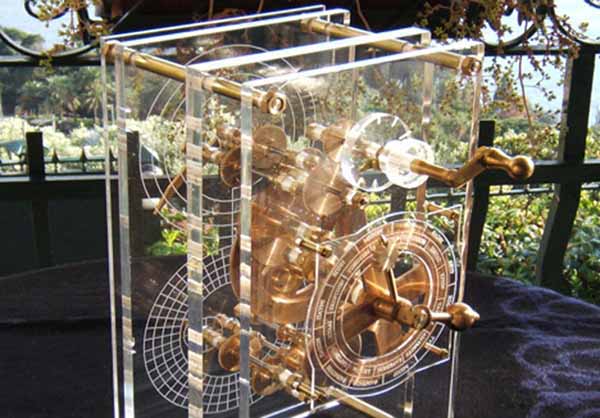

The knowledge of this technology was lost at some point in antiquity. Similar technological works later appeared in the medieval Byzantine and Islamic worlds, but works with similar complexity did not appear again until the development of mechanical astronomical clocks in Europe in the fourteenth century. All known fragments of the Antikythera mechanism are now kept at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, along with a number of artistic reconstructions and replicas of the mechanism to demonstrate how it may have looked and worked. Read more

The Antikythera Mechanism is an ancient alien artifact left behind by another civilization that was lived in the Mediterranean region. These were allegedly aliens who came here and for unknown reasons left the planet. Some believe they will return most believe they will not.

The 2,000-year-old Roman shipwreck that carried the Antikythera Mechanism - a precise mechanical model of the sun, moon and planets - is giving up new treasures, including a marble head thought to depict the Greek and Roman demigod Hercules. Live Science - July 6, 2022

Scientists and divers made the new discoveries after creating the first phases of a precise digital 3D model of the shipwreck, which sank near Antikythera, a Greek island in the southern Aegean Sea, in about the second quarter of the first century B.C. The digital model - which the scientists made with thousands of underwater photographs of the seafloor site, using a technique called photogrammetry - could help in the search for more pieces of the mysterious geared mechanism, the team said.

Scientists may have finally made a complete digital model for the Cosmos panel of a 2,000-year-old mechanical device called the Antikythera mechanism that's believed to be the world's first computer. Science Alert - March 13, 2021

The model recreates each gear and rotating dial to show how the planets, the sun, and the moon move across the Zodiac (the ancient map of the stars) on the front face and the phases of the moon and eclipses on the back. It replicates the now-outdated ancient Greek assumption that all of the heavens revolved around the Earth.

The Antikythera Mechanism: Scientists unlock mysteries of world's oldest 'computer' BBC - March 13, 2021

A 2,000-year-old device often referred to as the world's oldest "computer" has been recreated by scientists trying to understand how it worked. The Antikythera Mechanism has baffled experts since it was found on a Roman-era shipwreck in Greece in 1901. The hand-powered Ancient Greek device is thought to have been used to predict eclipses and other astronomical events. But only a third of the device survived, leaving researchers pondering how it worked and what it looked like. The back of the mechanism was solved by earlier studies, but the nature of its complex gearing system at the front has remained a mystery. Scientists from University College London (UCL) believe they have finally cracked the puzzle using 3D computer modeling. They have recreated the entire front panel, and now hope to build a full-scale replica of the Antikythera using modern materials.

Scientists solve another piece of the puzzling Antikythera mechanism Ars Technica - March 13, 2021

It took decades just to clean the device off, and in 1951, a British science historian named Derek J. de Solla Price began investigating the theoretical workings of the device. Based on X-ray and gamma ray photographs of the fragments, Price and physicist Charalampos Karakalos published a 70-page paper in 1959 in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. Based on those images, Price hypothesized that the mechanism had been used to calculate the motions of stars and planets - making it the first known analog computer.

Scientists announced that the new images had revealed much more of the original Greek transcription, which was subsequently translated. These images contained about 1000 characters to 2000 characters, or roughly 95 percent of the surviving text. A reconstruction of the device based on the high-resolution X-ray tomography conducted by the study confirmed it was an astronomical computer used to predict the positions of heavenly bodies in the sky. It's likely that the Antikythera mechanism once had 37 gears, of which 30 survive, and its front face had graduations showing the solar cycle and the zodiac, along with pointers to indicate the positions of the sun and moon.

Ancient skeleton discovered on Antikythera Shipwreck Science Daily - September 19, 2016

An international research team discovered a human skeleton during its ongoing excavation of the famous Antikythera Shipwreck (circa 65 B.C.). The shipwreck, which holds the remains of a Greek trading or cargo ship, is located off the Greek island of Antikythera in the Aegean Sea. The first skeleton recovered from the wreck site during the era of DNA analysis, this find could provide insight into the lives of people who lived 2100 years ago.

Antikythera Shipwreck Yields More Treasures Huffington Post - September 28, 2015

Archaeologists have discovered more than 50 artifacts hidden at the site of the ancient Greek shipwreck. The ancient Antikythera shipwreck -- a lavish Greek vessel that sank more than 2,000 years ago off the southwestern Aegean island of the same name -- isn't finished giving up its secrets. The shipwreck was found by Greek sponge fishermen in 1900. Over the past century, marine archaeologists have recovered marble and bronze statues and sculptures from the wreck, along with an odd clock-like device that some call the "world's oldest computer." Now an international team of archaeologists has recovered even more treasures -- a trove of more than 50 items, including a bronze armrest, remains of a bone flute, fine glassware, luxury ceramics, a pawn from an ancient board game and several pieces of the ship itself.