The Romani are an ethnic group living mostly in Europe and Americas. Romani are widely known in the English-speaking world by the exonym "Gypsies" (or Gipsies) and also as Romany, Romanies, Romanis, Roma or Roms; in their Romani language they are known collectively as Romane or Rromane (depending on the dialect).

Romani are widely dispersed, with their largest concentrated populations in Europe, especially the Roma of Central and Eastern Europe and Anatolia, followed by the Kale of Iberia and Southern France. They arrived in Europe from the Middle East in the 14th century, either separating from the Dom people or, at least, having a similar history; the ancestors of both the Romani and the Dom left the North India sometime between 6th and 11th century.

Since the 19th century, some Romani have also migrated to the Americas. There are an estimated one million Roma in the United States; and 800,000 in Brazil, most of whose ancestors emigrated in the nineteenth century from eastern Europe. Brazil also includes Romani descended from people deported by the government of Portugal during the Inquisition in the colonial era. In migrations since the late nineteenth century, Romani have also moved to Canada and countries in South America.

The Romani language is divided into several dialects, which add up to an estimated number of speakers larger than two million.The total number of Romani people is at least twice as large (several times as large according to high estimates). Many Romani are native speakers of the language current in their country of residence, or of mixed languages combining the two; those varieties are sometimes called Para-Romani.

New Archive Reclaims the Narrative of the Roma Smithsonian - January 31, 2019

The Roma are Europe's largest ethnic minority, but they have long been viewed as outsiders. In centuries past, the Roma were enslaved and massacred; today, they are vilified by politicians, denied access to housing and subjected to racist attacks. Now a new digital archive hopes to counter anti-Roma sentiment by highlighting the group's rich history and culture. Some 5,000 objects are contained within the RomArchive, among them photographs, video and sound recordings, and texts, which have been organized into several curated sections.

Genetic findings in 2012 suggest they originated in northwest India and migrated as a group. According to a genetic study in 2012, the ancestors of present scheduled tribes and scheduled caste populations of northern India, traditionally referred to collectively as the Doma, are the likely ancestral populations of modern European Roma.

In December 2012, additional findings appeared to confirm the "Roma came from a single group that left northwestern India about 1,500 years ago. They reached the Balkans about 900 years ago, and then spread throughout Europe. The team found that, despite some isolation, the Roma were "genetically similar to other Europeans." Contemporary populations suggested as sharing a close relationship to the Romani are the Dom people of Western Asia and North Africa, and the Banjara of India.

Genetic evidence supports the mediaeval migration from India. The Romani have been described as "a conglomerate of genetically isolated founder populations", while a number of common Mendelian disorders among Romanies from all over Europe indicates "a common origin and founder effect".

A study from 2001 by Gresham et al. suggests "a limited number of related founders, compatible with a small group of migrants splitting from a distinct caste or tribal group". The same study found that "a single lineage ... found across Romani populations, accounts for almost one-third of Romani males."

A 2004 study by Morar et al. concluded that the Romani population "was founded approximately 32-40 generations ago, with secondary and tertiary founder events occurring approximately 16-25 generations ago". The discovery in 2009 of the "Jat mutation" that causes a type of glaucoma in Romani populations suggests that the Romani people are the descendants of the Jat people found in Northern India and Pakistan. This relation to Jats had earlier been suggested by Michael Jan de Goeje in 1883. The 2009 glaucoma study, however, contradicts an earlier study that compared the most common haplotypes found in Romani groups with those found in Jatt Sikhs and Jats from Haryana and found no matches.

They may have emerged from the modern Indian state of Rajasthan, migrating to the northwest (the Punjab region, Sindh and Baluchistan of modern-day Pakistan and India) around 250 BC. In the centuries spent here, there may have been close interaction with such established groups as the Rajputs and the Jats. Their subsequent westward migration, possibly in waves, is now believed to have occurred beginning in about AD 500[dubious - discuss].

It has also been suggested that emigration from India may have taken place in the context of the raids by Mahmud of Ghazni As these soldiers were defeated, they were moved west with their families into the Byzantine Empire. The 11th century terminus post quem is due to the Romani language showing unambiguous features of the Modern Indo-Aryan languages, precluding an emigration during the Middle Indic period.

The first historical records of the Romani reaching south-eastern Europe are from the 14th century. In 1322, an Irish Franciscan monk, Symon Semeonis encountered a migrant group, "the descendants of Cain", outside the town of Heraklion (Candia), in Crete. Symon's account is probably the earliest surviving description by a Western chronicler of the Romani people in Europe. In 1350, Ludolphus of Sudheim mentioned a similar people with a unique language whom he called Mandapolos, a word which some theorize was derived from the Greek word mantes (meaning prophet or fortune teller).

Around 1360, a fiefdom, called the Feudum Acinganorum was established in Corfu, which mainly used Romani serfs and to which the Romani on the island were subservient.

By 1424, they were recorded in Germany; and by the 16th century, Scotland and Sweden. Some Romani migrated from Persia through North Africa, reaching the Iberian Peninsula in the 15th century[. The two currents met in France. According to a 2012 genomic study, the Romani reached the Balkans as early as the 12th century.

Their early history shows a mixed reception. Although 1385 marks the first recorded transaction for a Romani slave in Wallachia, they were issued safe conduct by Sigismund of the Holy Roman Empire in 1417.[97] Romanies were ordered expelled from the Meissen region of Germany in 1416, Lucerne in 1471, Milan in 1493, France in 1504, Catalonia in 1512, Sweden in 1525, England in 1530, and Denmark in 1536. In 1510, any Romani found in Switzerland were ordered to be put to death, with similar rules established in England in 1554, and Denmark in 1589, whereas Portugal began deportations of Romanies to its colonies in 1538.

Later, a 1596 English statute, however, gave Romanies special privileges that other wanderers lacked; France passed a similar law in 1683. Catherine the Great of Russia declared the Romanies "crown slaves" (a status superior to serfs), but also kept them out of certain parts of the capital. In 1595, Stefan Razvan overcame his birth into slavery, and became the Voivode (Prince) of Moldavia.

An 1852 Wallachian poster advertising an auction of Romani slaves in Bucharest. Romani could be kept as slaves in Wallachia and Moldavia, until abolition in 1856. Elsewhere in Europe, they were subject to ethnic cleansing, abduction of their children, and forced labor. In England, Romani were sometimes expelled from small communities or hanged; in France, they were branded and their heads were shaved; in Moravia and Bohemia, the women were marked by their ears being severed. As a result, large groups of the Romani moved to the East, toward Poland, which was more tolerant, and Russia, where the Romani were treated more fairly as long as they paid the annual taxes.

Romani began emigrating to North America in colonial times, with small groups recorded in Virginia and French Louisiana. Larger-scale Roma emigration to the United States began in the 1860s, with groups of Romnaichal from Great Britain. The largest number immigrated in the early 1900s, mainly from the Vlax group of Kalderash. Many Romani also settled in South America.

During World War II, the Nazis and the Ustasa embarked on a systematic genocide of the Romani, a process known in Romani as the Porajmos. Romanies were marked for extermination and sentenced to forced labor and imprisonment in concentration camps.

They were often killed on sight, especially by the Einsatzgruppen (mobile killing units) on the Eastern Front. The total number of victims has been variously estimated at between 220,000 to 1,500,000; even the lowest number would make the Porajmos one of the largest mass killings in history.

In Communist Eastern Europe, Romanies experienced assimilation schemes and restrictions on cultural freedom. The Romani language and Romani music were banned from public performance in Bulgaria. In Czechoslovakia, they were labeled a "socially degraded stratum," and Romani women were sterilized as part of a state policy to reduce their population. This policy was implemented with large financial incentives, threats of denying future welfare payments, with misinformation, or after administering drugs.

An official inquiry from the Czech Republic, resulting in a report (December 2005), concluded that the Communist authorities had practiced an assimilation policy towards Romanies, which "included efforts by social services to control the birth rate in the Romani community". "The problem of sexual sterilisation carried out in the Czech Republic, either with improper motivation or illegally, exists," said Czech Public Defender of Rights, recommending state compensation for women affected between 1973 and 1991. New cases were revealed up until 2004, in both the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Germany, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland "all have histories of coercive sterilization of minorities and other groups."

The traditional Romanies place a high value on the extended family. Virginity is essential in unmarried women. Both men and women often marry young; there has been controversy in several countries over the Romani practice of child marriage. Romani law establishes that the man's family must pay a bride price to the bride's parents, but only traditional families still follow this rule.

Once married, the woman joins the husband's family, where her main job is to tend to her husband's and her children's needs, as well as to take care of her in-laws. The power structure in the traditional Romani household has at its top the oldest man or grandfather, and men in general have more authority than women. Women gain respect and authority as they get older. Young wives begin gaining authority once they have children.

Romani social behavior is strictly regulated by Hindu purity laws ("marime" or "marhime"), still respected by most Roma (and by most older generations of Sinti). This regulation affects many aspects of life, and is applied to actions, people and things: parts of the human body are considered impure: the genital organs (because they produce emissions), as well as the rest of the lower body. Clothes for the lower body, as well as the clothes of menstruating women, are washed separately. Items used for eating are also washed in a different place. Childbirth is considered impure, and must occur outside the dwelling place. The mother is considered impure for forty days after giving birth.

Death is considered impure, and affects the whole family of the dead, who remain impure for a period of time. In contrast to the practice of cremating the dead, Romani dead must be buried. Cremation and burial are both known from the time of the Rigveda, and both are widely practiced in Hinduism today (although the tendency for higher caste groups is to burn, while lower caste groups in South India tend to bury their dead). Some animals are also considered impure, for instance cats because they lick themselves.

Romanipen (also romanypen, romanipe, romanype, romanimos, romaimos, romaniya) is a complicated term of Romani philosophy that means totality of the Romani spirit, Romani culture, Romani Law, being a Romani, a set of Romani strains.

An ethnic Romani is considered to be a Gadjo (non-Romani) in the Romani society if he has no Romanipen. Sometimes a non-Romani may be considered to be a Romani if he has Romanipen, (usually that is an adopted child). As a concept, Romanipen has been the subject of interest to numerous academic observers. It has been hypothesized that it owes more to a framework of culture rather than simply an adherence to historically received rules.

The ancestors of modern day Romani people were previously Hindu but adopted Christianity or Islam depending on their respective countries due to missionary activities.

Blessed Ceferino Gimenez Malla is considered a patron saint of the Romani people in Roman Catholicism. Saint Sarah, or Kali Sara, has also been worshipped as a patron saint in the same manner as the Blessed Ceferino Gimenez Malla, but a transition has occurred in the 21st century, whereby Kali Sara is understood as an Indian deity brought from India by the refugee ancestors of the Roma people, thereby removing any Christian association. Saint Sarah is progressively being considered as "a Romani Goddess, the Protectress of the Roma" and an "indisputable link with Mother India".

Romanies often adopt the dominant religion of their host country in the event that a ceremony associated with a formal religious institution is necessary, such as a baptism or funeral (their particular belief systems and indigenous religion and worship remain preserved regardless of such adoption processes). The Roma continue to practice "Shaktism", a practice with origins in India, whereby a female consort is required for the worship of a god. Adherence to this practice means that for the Roma who worship a Christian God, prayer is conducted through the Virgin Mary, or her mother, Saint Anne - Shaktism continues over one thousand years after the people's separation from India.

Besides the Roma elders, who serve as spiritual leaders, priests, churches, or bibles do not exist among the Romanies - the only exception is the Pentecostal Roma.

For the Roma communities that have resided in the Balkans for numerous centuries, often referred to as "Turkish Gypsies", the following histories apply for religious beliefs,

In northwestern Bulgaria, in addition to Sofia and Kyustendil, Islam has been the dominant religion; however, in the independent Bulgarian state, a major conversion to Eastern Orthodox Christianity has occurred. In southwestern Bulgaria (Pirin Macedonia), Islam is also the dominant religion, with a smaller section of the population, declaring themselves as "Turks", continuing to mix ethnicity with Islam.

The majority are mostly Orthodox Christians. In the South East they have a small community that are Muslim and also speak Turkish.

The descendants of groups, such as Sepecides or Sevljara, Kalpazaja, Filipidzi and others, living in Athens, Thessaloniki, central Greece and Aegean Macedonia are mostly Orthodox Christians, with Islamic beliefs held by a minority of the population. Following the Peace Treaty of Lausanne of 1923, many Muslims resettled Turkey, in the consequent population exchange between Turkey and Greece.

Albania's Roma people are all Muslims.

Macedonia - The majority of Roma people believe in Islam.

Most Roma people in Serbia are Muslim, but the Gurbeti community, as it has been designated, believes in Christianity.

The vast majority of the Roma population in what has become Kosovo is Muslim.

Following the World War II, a large number of Muslim Roma relocated to Croatia (the majority moved from Kosovo).

Ukraine and Russia also consist of Roma Muslim populations, as the families of Balkans migrants continue to live in these locations. The descendants' ancestors settled on the Crimean peninsula during the 17th and 18th centuries, but most descendants migrated to Ukraine, southern Russia and the Povolzhie (along the Volga River). Formally, Islam is the religion that these communities align themselves with and the people are recognized for its staunch preservation of the Romani language and identity.

Most Eastern European Romanies are Roman Catholic, Orthodox Christian, or Muslim. Those in Western Europe and the United States are mostly Roman Catholic or Protestant - in southern Spain, many Romanies are Pentecostal), but this is a small minority that has emerged in contemporary times

In Egypt, the Romanies are split into Christian and Muslim populations - for countless years, dance has been considered a religious procedure for the Egyptian Romanies.

�Romani music (often referred to as Gypsy or Gipsy music, which is considered a derogatory term) is the music of the Romani people, who have their origins in Northern India, but today live mostly in Europe.

Typically nomadic, the Romani people have long acted as wandering entertainers and tradesmen. In all the places Romanies live they have become known as musicians. The wide distances travelled have introduced a multitude of influences, starting with Indian roots and adding elements of Greek, Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Serbian, Czech, Slavic, Romanian, German, French and Spanish musical forms.

Romani music characteristically has vocals that tend to be soulful and declamatory, and the music often incorporates prominent glissandi (slides) between notes. Instrumentation varies widely according to the region the music comes from.

There is a strong tradition of Romani music in Central and Eastern Europe, notably in countries such as Hungary, Romania and the former Yugoslavia. The quintessentially Spanish flamenco is to a very large extent the music (and dance, or indeed the culture) of the Romani people of Andalusia.

Apart from Romani music for local use, in Eastern Europe a separate Romani music originated for entertainment in restaurants and at parties and celebrations. This music drew its themes from Hungarian, Romanian, Russian and other sources of Romani origin, but was more sophisticated and became enormously popular in places like Budapest and Vienna. Later on it gained popularity in Western Europe, where many Romani orchestras were active, playing sophisticated melodies of East European origin.

Romani is any of several languages of the Romani people belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European language family. According to Ethnologue, seven varieties of Romani are divergent enough to be considered languages of their own. The largest of these are Vlax Romani (about 900,000 speakers), Balkan Romani (700,000), Carpathian Romani (500,000) and Sinte Romani (300,000). Some Romani communities speak mixed languages based on the surrounding language with retained Romani-derived vocabulary - these are known by linguists are Para-Romani varieties, rather than dialects of the Romani language itself. The differences between various varieties can be as big as, for example, differences between various Slavic languages.

The Romani language is sometimes considered a group of dialects or a collection of related languages that comprise all the members of a single genetic subgroup. According to Ethnologue, seven varieties of Romani are divergent enough to be considered languages of their own. The largest of these are Vlax Romani (about 900,000 speakers), Balkan Romani (700,000), Carpathian Romani (500,000)and Sinte Romani (300,000).

Some Romani communities, especially those on the western periphery of the Romani diaspora, use mixed languages with Romani-derived vocabulary rather than Romani proper. These varieties are known by linguists as Para-Romani.

One of the most enduring persecutions against the Romani people was the enslaving of the Romanies. In the Byzantine Empire, they were slaves of the state and it seems the situation was the same in Bulgaria and Serbia until their social organization was destroyed by the Ottoman conquest. Slavery existed on the territory of present-day Romania from before the founding of the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia in 13th-14th century, until it was abolished in stages during the 1840s and 1850s. Legislation decreed that all the Romanies living in these states, as well as any others who would immigrate there, were slaves. Most of the slaves were of Roma (Gypsy) ethnicity.

The exact origins of slavery in the Danubian Principalities are not known. There is some debate over whether the Romani people came to Wallachia and Moldavia as free men or as slaves. Historian Nicolae Iorga associated the Roma people's arrival with the 1241 Mongol invasion of Europe and considered their slavery as a vestige of that era, the Romanians taking the Roma from the Mongols as slaves and preserving their status. Other historians consider that they were enslaved while captured during the battles with the Tatars. The practice of enslaving prisoners may also have been taken from the Mongols.

While it is possible that some Romani people were slaves or auxiliary troops of the Mongols or Tatars, the bulk of them came from south of the Danube at the end of the 14th century, some time after the foundation of Wallachia. By then, the institution of slavery was already established in Moldavia and possibly in both principalities, but the arrival of the Roma made slavery a widespread practice. The Tatar slaves, smaller in numbers, were eventually merged into the Roma population.

The arrival of some branches of the Romani people in Western Europe in the 15th century was precipitated by the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans. Although the Romanies themselves were refugees from the conflicts in southeastern Europe, they were mistaken by the local population in the West, because of their foreign appearance, as part of the Ottoman invasion (the German Reichstags at Landau and Freiburg in 1496-1498 declared the Romanies as spies of the Turks).

In Western Europe, this resulted in a violent history of persecution and attempts of ethnic cleansing until the modern era. As time passed, other accusations were added against local Romanies (accusations specific to this area, against non-assimilated minorities), like that of bringing the plague, usually sharing their burden together with the local Jews.

One example of official persecution of the Romani is exemplified by The Great Roundup of Spanish Romanies (Gitanos) in 1749. The Spanish monarchy ordered a nationwide raid that led to separation of families and placement of all able-bodied men into forced labor camps.

Later in the 19th century, Romani immigration was forbidden on a racial basis in areas outside Europe, mostly in the English-speaking world (in 1885 the United States outlawed the entry of the Roma) and also in some South American countries (in 1880 Argentina adopted a similar policy).

The persecution of the Romanies reached a peak during World War II in the Porajmos, the genocide perpetrated by the Nazis during the Holocaust. In 1935, the Nuremberg laws stripped the Romani people living in Nazi Germany of their citizenship, after which they were subjected to violence, imprisonment in concentration camps and later genocide in extermination camps. The policy was extended in areas occupied by the Nazis during the war, and it was also applied by their allies, notably the Independent State of Croatia, Romania and Hungary.

Because no accurate pre-war census figures exist for the Romanis, it is impossible to accurately assess the actual number of victims. Ian Hancock, director of the Program of Romani Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, proposes a figure of up to a million and a half, while an estimate of between 220,000 and 500,000 was made by Sybil Milton, formerly senior historian of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. In Central Europe, the extermination in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was so thorough that the Bohemian Romani language became extinct.

In the Habsburg Monarchy under Maria Theresa (1740-1780), a series of decrees tried to force the Romanies to permanently settle, removed rights to horse and wagon ownership (1754), renamed them as "New Citizens" and forced Romani boys into military service if they had no trade (1761), forced them to register with the local authorities (1767), and prohibited marriage between Romanies (1773). Her successor Josef II prohibited the wearing of traditional Romani clothing and the use of the Romani language, punishable by flogging.

In Spain, attempts to assimilate the Gitanos were under way as early as 1619, when Gitanos were forcibly settled, the use of the Romani language was prohibited, Gitano men and women were sent to separate workhouses and their children sent to orphanages. Similar prohibitions took place in 1783 under King Charles III, who prohibited the nomadic lifestyle, the use of the Calo language, Romani clothing, their trade in horses and other itinerant trades. The use of the word gitano was also forbidden to further assimilation. Ultimately these measures failed, as the rest of the population rejected the integration of the Gitanos.

Other examples of forced assimilation include Norway, where a law was passed in 1896 permitting the state to remove children from their parents and place them in state institutions. This resulted in some 1,500 Romani children being taken from their parents in the 20th century.

Discrimination against the Romani people has continued to the present day, although efforts are being made to address them. Amnesty International reports continued instances of Antizigan discrimination during the 20th Century, particularly in Bulgaria, Greece, Italy, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, and Kosovo.

The Romanis of Kosovo have been severely persecuted by ethnic Albanians since the end of the Kosovo War, and the region's Romani community is regarded to be for the most part annihilated.

Czechoslovakia carried out a policy of sterilization of Romani women, starting in 1973. The dissidents of the Charter 77 denounced it in 1977-78 as a "genocide", but the practice continued through the Velvet Revolution of 1989.

A 2005 report by the Czech government's independent ombudsman, Otakar Motejl, identified dozens of cases of coercive sterilization between 1979 and 2001, and called for criminal investigations and possible prosecution against several health care workers and administrators.

In 2008, following the brutal murder of a woman in Rome at the hands of a young man from a local Romani encampment, the Italian government declared that Italy's Romani population represented a national security risk and that swift action was required to address the emergenza nomadi (nomad emergency). Specifically, officials in the Italian government accused the Romanies of being responsible for rising crime rates in urban areas. One police raid in 2007 freed many of the children belonging to a Romani gang who used to steal by day, and who were locked in a shed by night by members of the gang.

The 2008 deaths of Cristina and Violetta Djeordsevic, two Roma children who drowned while Italian beach-goers remained unperturbed, brought international attention to the relationship between Italians and the Roma people.

In the summer of 2010 French authorities demolished at least 51 illegal Roma camps and began the process of repatriating their residents to their countries of origin. This followed tensions between the French state and Roma communities, which had been heightened after French police opened fire and killed a traveller who drove through a police checkpoint, hitting an officer, and attempted to hit two more officers at another checkpoint. In retaliation a group of Roma, armed with hatchets and iron bars, attacked the police station of Saint-Aignan, toppled traffic lights and road signs and burned three cars.

The French government has been accused of perpetrating these actions to pursue its political agenda. EU Justice Commissioner Viviane Reding stated that the European Commission should take legal action against France over the issue, calling the deportations "a disgrace". Purportedly, a leaked file dated August 5, sent from the Interior Ministry to regional police chiefs included the instruction: "Three hundred camps or illegal settlements must be cleared within three months, Roma camps are a priority.

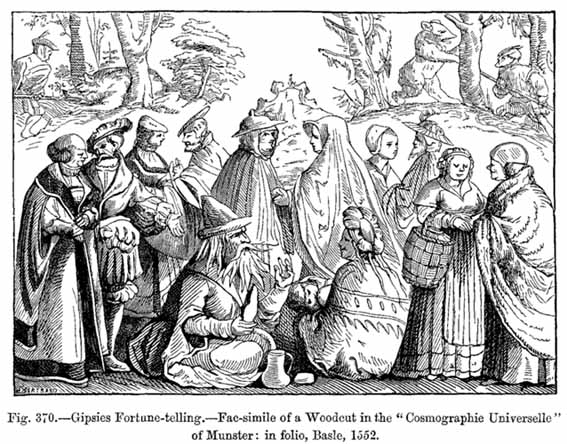

Many fictional depictions of Romani people in literature and art present romanticized narratives of their supposed mystical powers of fortune telling or their supposed irascible or passionate temper paired with an indomitable love of freedom and a habit of criminality.

The Romani ethnicity is often used for characters in contemporary fantasy literature. In such literature, the Romani are often portrayed as possessing archaic occult knowledge passed down through the ages. This frequent use of the ethnicity has given rise to 'gypsy archetypes' in popular contemporary literature. Read more

Gypsy Fortune Telling